#89 Why Exercise Intensity Matters for Longevity | CrossFit for Health 2024

This episode is available in a convenient podcast format.

These episodes make great companion listening for a long drive.

The Omega-3 Supplementation Guide

A blueprint for choosing the right fish oil supplement — filled with specific recommendations, guidelines for interpreting testing data, and dosage protocols.

I recently had the privilege of presenting at the CrossFit Health Summit, where I described a constellation of factors that influence longevity – with special emphasis on the pivotal role of vigorous exercise throughout life.

Given that CrossFit has become almost synonymous with the type of intense, demanding workouts that are central to our discussion, the venue provided an ideal audience for exploring the profound impacts of this fitness approach.

- 00:52 - Why "below normal" cardio may be a great starting point (for adding years to your life)

- 02:47 - The simple math of 45 days of life extension (per 1 mL/kg/min VO2max)

- 02:54 - Is there an upper limit to the longevity benefits of VO2 max?

- 03:52 - Why poor cardiovascular fitness is nearly as bad as a chronic disease

- 04:32 - Why zone 2 training may not improve VO2 max (for some people)

- 05:47 - Protocols for improving VO2 max quickly

- 06:50 - How to estimate VO2 max in 12 minutes (without a lab)

- 07:47 - What it takes to reverse 20 years of heart aging

- 10:21 - Blood pressure benefits of vigorous exercise

- 10:51 - The role of blood pressure in dementia

- 11:09 - The BDNF brain benefits of high-intensity exercise

- 11:46 - The signaling role of lactate production by muscle

- 13:54 - How training effortfully improves focus & attention

- 14:45 - Protocols for maximizing BDNF from training (HR training targets and duration)

- 15:04 - Anti-cancer effects of vigorous exercise

- 15:52 - Why shear stress kills circulating tumor cells — an experiment in three cell lines

- 16:14 - Why reducing circulating tumor cells likely greatly increases survival

- 16:41 - What if you exercise in short bursts all day long?

- 17:47 - Why "exercise snacks" are a crucial pre- and post-mealtime activity

- 18:30 - The best ways to improve mitochondrial biogenesis — and metabolism

- 19:28 - The mortality benefits of breaking up sedentary time

- 23:58 - Why the protein RDA is too low (and the flawed experiments that lead to that)

- 25:00 - How much protein is needed for muscle?

- 26:49 - Does omega-3 reduce muscle atrophy?

- 28:22 - Why we should lift for aging and to prevent the 8% per decade decline of muscle

- 29:45 - Is lifting heavy necessary for gaining muscle?

- 30:47 - What the sauna has in common with exercise

- 32:27 - Does the sauna enhance the benefits of exercise?

- 34:26 - How heat shock proteins prevent plaque aggregation & slow muscle atrophy

- 36:05 - Can sauna after resistance training boost hypertrophy?

- 36:48 - Sauna parameters (temperature, duration, frequency, & humidity)

- 37:42 - Comparing traditional saunas to infrared

- 38:42 - Are hot baths a valid sauna alternative?

- 39:54 - Audience Q&A

- 40:02 - Is EPA or DHA responsible for omega-3's effects on disuse atrophy?

- 41:36 - Are endurance athletes at risk for cardiovascular injury?

- 42:40 - What mechanisms are responsible for sauna's benefits?

- 44:50 - Is a sauna temperature above 200 °F too hot?

- 47:14 - My recommended sauna temperature & duration

Here are some of the key takeaways:

The predictive power of cardiorespiratory fitness on lifespan.

VO2 max, a key measure of cardiorespiratory fitness, robustly predicts lifespan. Having a lower VO2 max is associated with a shorter lifespan, but the silver lining is that vigorous exercise can lead to notable improvements. Here's how VO2 max, based on observational and associative data, can impact your years:

- From low to normal: May extend your life by more than two years.

- From low to high normal: May extend your life by approximately three years.

"Each unit increase in your VO2 max is associated with a 45-day increase in life expectancy."- Dr. Rhonda Patrick Click To Tweet

The benefits continue to accumulate from there. Research shows there's no upper limit to the longevity gains from improving VO2 max, with each unit increase potentially extending lifespan by about 45 days.

What science says about reversing the effects of aging on the heart.

As we age, our heart undergoes significant structural changes – some as early as our 40s and 50s, especially if we're sedentary. The heart's walls thicken, the valves stiffen, and eventually, there's atrophy, increasing our risk for cardiovascular disease. However, vigorous exercise can forestall and even reverse these structural changes. At the end of an amazing intervention trial where sedentary people in their 50s engaged in regular, vigorous exercise for two years, their hearts looked, in some aspects, like those of people two decades younger.

Here's a closer look at the regimen they followed:

- Two-year commitment: Participants adhered to a structured, graduated training regimen, culminating in five to six hours of physical activity per week.

- Norwegian 4x4 interval training: They performed four minutes of intense activity at 95% of peak heart rate, followed by three minutes of active recovery at 60%-75% peak heart rate, repeated four times. Initially, they did it once a week, later increasing to twice a week, and eventually going back to just once weekly.

- Light aerobic activity on recovery days: On days following interval training sessions, they engaged in light exercises lasting 20 to 30 minutes.

- Endurance base building: The regimen incorporated an hour-long (or longer) endurance session and a 30-minute base pace session each week.

- Strength training sessions: Participants engaged in strength training twice weekly.

Vigorous exercise reduces blood pressure – comparable to the effects of antihypertensive drugs.

High blood pressure is like a gateway disease: Even slight blood pressure elevations can damage your heart and increase your risk for cardiovascular disease. However, high blood pressure also harms tiny blood vessels in your brain, increasing your risk for dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Robust data from randomized controlled trials point to the effectiveness of regular vigorous exercise in reducing high blood pressure, potentially offering a drug-free approach to managing the condition.

Adequate protein intake is essential for preserving lean muscle mass, especially as we age.

Dietary protein intake is one of the primary stimuli for building and maintaining muscle. The recommended dietary allowance for protein intake is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight (about 0.36 grams per pound) daily – roughly 55 grams for a 150-pound adult. Unfortunately, this recommendation is based on 40-year-old investigative techniques and data. Modern assessments indicate that aiming for 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight will likely provide the greatest benefit, potentially preventing age-related muscle losses.

Diet alone won't help you build and maintain muscle.

For that, you need to include resistance training, which challenges your muscles, inducing metabolic and mechanical stressors that promote growth and strength. If training with weights seems daunting, it's encouraging to know that engaging in resistance exercise just one to three days a week can build muscle mass and strength, even in older adults. And using heavy weights isn't a requirement: Lighter loads with more repetitions can have potent effects.

Omega-3s may help maintain muscle mass during periods of disuse – like when recovering from an injury.

Perhaps best known for their anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and cardioprotective roles, omega-3 fatty acids support and maintain human health in various ways, from the brain to the heart and more. However, some recent research points to some surprising effects of omega-3s: High doses seem to mitigate anabolic resistance. Women who preloaded with high-dose omega-3s lost roughly half as much muscle during immobilization as those who didn't. And other studies suggest that omega-3s promote functional improvements in older adults.

Heat exposure mimics (and potentiates) the effects of moderate-intensity exercise.

Whether in a sauna, a hot tub, or a home bath, heat exposure stresses your body, increasing your heart rate, blood pressure, and core body temperature – much like exercise. The downstream effects of these stress responses include reduced heart rate and blood pressure and overall improvements in cardiovascular health. For even greater benefit, you can piggyback a robust workout with a heat session, effectively extending the workout and potentiating its effects.

Heat exposure also turns on the activity of heat shock proteins, protecting the brain and muscles.

Heat shock proteins ensure that the protein synthesis machinery inside your cells works appropriately. If these processes become disordered, the proteins can misfold and aggregate, forming clumps. Protein aggregation is a hallmark of many brain diseases, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Heat shock proteins prevent misfolding and aggregation, reducing the risk of these diseases and others. These important proteins also influence muscle health, reducing wasting during periods of disuse and promoting gains with resistance training.

I also discuss the brain benefits of lactate (it's not just a metabolic byproduct), the cancer-preventing effects of exercise, squeezing more vigorous activity into your day, and many other topics I know you'll find interesting! There's a lot to unpack in this presentation, and you won't want to miss it.

People mentioned:

- Dr. Martin Gibala

- Dr. Ben Levine

- Dr. Stuart Phillips

- Dr. Chris McGlory

- Dr. Brad Schoenfeld

- Dr. Jari Laukkanen

Related FoundMyFitness resources:

Articles:

Episodes & Clips:

- Dr. Martin Gibala: The Science of Vigorous Exercise — From VO2 Max to Time Efficiency of HIIT

- The Longevity & Brain Benefits of Vigorous Exercise | Dr. Rhonda Patrick

- Brad Schoenfeld, PhD: Resistance Training for Time Efficiency, Body Composition & Maximum Hypertrophy

- This Type of Exercise Reverses Heart Aging, Lowers Blood Pressure, & Has Anti-Cancer Effects

- Rhonda Patrick's Sauna Routine (temperature, duration, & hydration protocols)

- Why You DON'T Need to Lift Heavy or Hit Failure to Build Muscle | Dr. Brad Schoenfeld

Other related links:

- The Cognitive Enhancement Blueprint (bdnfprotocols.com) - This guide is your tactical checklist for better brain aging. Expect to learn specific exercise, omega-3, and heat stress protocols for boosting BDNF.

-

Why "below normal" cardio may be a great starting point (for adding years to your life)

-

The simple math of 45 days of life extension (per 1 mL/kg/min VO2max)

-

Is there an upper limit to the longevity benefits of VO2 max?

-

Why poor cardiovascular fitness is nearly as bad as a chronic disease

-

Why zone 2 training may not improve VO2 max (for some people)

-

Protocols for improving VO2 max quickly

-

How to estimate VO2 max in 12 minutes (without a lab)

-

What it takes to reverse 20 years of heart aging

-

Blood pressure benefits of vigorous exercise

-

The role of blood pressure in dementia

-

The BDNF brain benefits of high-intensity exercise

-

The signaling role of lactate production by muscle

-

How training effortfully improves focus & attention

-

Protocols for maximizing BDNF from training (HR training targets and duration)

-

Anti-cancer effects of vigorous exercise

-

Why shear stress kills circulating tumor cells — an experiment in three cell lines

-

Why reducing circulating tumor cells likely greatly increases survival

-

What if you exercise in short bursts all day long?

-

Why "exercise snacks" are a crucial pre- and post-mealtime activity

-

The best ways to improve mitochondrial biogenesis — and metabolism

-

The mortality benefits of breaking up sedentary time

-

Why the protein RDA is too low (and the flawed experiments that lead to that)

-

How much protein is needed for muscle?

-

Does omega-3 reduce muscle atrophy?

-

Why we should lift for aging and to prevent the 8% per decade decline of muscle

-

Is lifting heavy necessary for gaining muscle?

-

What the sauna has in common with exercise

-

Does the sauna enhance the benefits of exercise?

-

How heat shock proteins prevent plaque aggregation & slow muscle atrophy

-

Can sauna after resistance training boost hypertrophy?

-

Sauna parameters (temperature, duration, frequency, & humidity)

-

Comparing traditional saunas to infrared

-

Are hot baths a valid sauna alternative?

-

Audience Q&A

-

Is EPA or DHA responsible for omega-3's effects on disuse atrophy?

-

Are endurance athletes at risk for cardiovascular injury?

-

What mechanisms are responsible for sauna's benefits?

-

Is a sauna temperature above 200 °F too hot?

-

My recommended sauna temperature & duration

Hi, Crossfit. Yeah. So today we're going to be talking about how to maximize your healthspan, and I'm going to focus on three really important lifestyle behaviors.

We're going to talk about exercise, we're going to talk about the strength of resistance training and the power of deliberate heat exposure. That's my disclosure. So focusing on exercise, it's going to be really vigorous exercise.

We're going to talk about the importance of vigorous-intensity exercise, going like 80% max heart rate or more. We're going to talk about the brain benefits, we're going to talk about cardiovascular benefits, cancer, a little bit, exercise snacks. Then we're going to get into some muscle biology, a little bit, the importance of protein, resistance training, and then into deliberate heat exposure and sauna, and how that can synergize with both exercise and also with resistance training.

So let's start with the vigorous exercise. So, cardiorespiratory fitness is probably one of the most important biomarkers that we can measure via VO2 max. So maximal oxygen uptake during maximal exercise, that really indicates our fitness levels.

Right. But it also is probably one of the most important indicators of longevity. And there's been studies that have shown probably the most important, I would say the maximal benefits you get from improving your cardiorespiratory fitness go from, if you're below normal, and you go anywhere above that. So if you're a below normal VO2 max and you go just to normal, you're getting about a 2.1-year increase in life expectancy.

If you go below normal to high normal, which is about where half the population lies, then you're getting an almost three-year increase in life expectancy. And then if you go to, like, more of an elite level, so you're getting into, like, above the upper limit, that's a five-year increase in life expectancy compared to where you were when you were below normal. And about each unit increase in your VO2 max is associated with a 45-day increase in life expectancy.

And there was a really important study published in JAMA, a journal. This was, like, in 2018, and there's now been a couple of papers since then. But I really liked this study because it really sort of showed that there wasn't an upper limit on the longevity benefit of improving your VO2 max.

And so people that were in the elite group of VO2 max. So this is, we're talking like, the top 2.1%. Those people had a 80% lower all-cause mortality compared to people that were in the lower I would say basically the lower 20% or so VO2 max.

So if you were not the elite, but you still were really fit, you had a high VO2 max, you had great cardiorespiratory fitness, you still had a 20% increase in all-cause mortality compared to the elite athletes, like the people that had the really good VO2 max. So there seemed to really be a benefit at every level. But what was so interesting about this study was that people in that low fitness group, they had a low VO2 max.

Their risk of death and all-cause mortality was similar to having diseases like type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease. It was similar to smoking. I mean, these things that everyone focuses on, these disease states that everyone focuses on, and we know they're bad, we know they decrease life quality, they decrease lifespan.

But what people don't focus on is how not being physically fit, not having a good cardiorespiratory fitness, is almost like having one of those diseases. And I really think that puts it into perspective how important VO2 max is for longevity.

So how do you improve your VO2 max? How do you improve your cardiorespiratory fitness? Well, aerobic exercise is definitely one of the best ways to do that.

What type of aerobic exercise? I think it's pretty clear that high-intensity interval training is one of the best ways to improve your VO2 max. And particularly when you do longer intervals. Yes, you can improve your cardiorespiratory fitness with any type of aerobic exercise, particularly if you're starting from being sedentary and then going up, right?

But there was a really important study that was published, a large, large population of people, that showed people that are doing moderate intensity, sort of zone two training. This is the kind of exercise that is more enjoyable – you can go for a run and you can still have somewhat of a conversation. You're breathy.

Those people are doing two and a half hours per week. They're meeting the guidelines. And yet they couldn't improve their VO2 max, about 40% of those people. So you're talking like, half the population here.

Until they added in some high-intensity interval training. And once they added in some high-intensity interval training, they were able to improve their VO2 max. And so I really think, again, this highlights the importance of really trying to get your heart rate up to at least 80% max heart rate or more.

The question is, well, what kind of protocols are best for improving VO2 max? I mentioned longer intervals, I think probably… so, Dr. Martin Gibala does a lot of this research at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada. And he has talked about one minute being sort of like probably the minimal effective dose for improving VO2 max, at least getting some 1-minute intervals and repeating that four or five times.

But I think one of the most evidence-based protocols, if you look in the literature out there for improving cardiorespiratory fitness, is the Norwegian four-by-four protocol. And this is where you do four minutes of the most…You maintain the intensity that you can for that entire four minutes.

So you don't want to go out all out in the first minute. So you want to be able to pace yourself. It's four minutes of, you know, high-intensity exercise followed by three minutes of recovery, and you do that four times.

So it's a pretty brutal workout. But it's the Norwegian four-by-four, and it's one of the best ways to improve cardiorespiratory fitness as measured by VO2 max. If you are interested in measuring your VO2 max, the best way to do it, obviously, would be directly to measure it, go to a lab that measures VO2 max.

If you don't have access to one of those, you don't want to pay or whatever. There's a good evidence-based way of estimating VO2 max. And that's really the 12-mile run test or walk test, depending on your fitness level.

And essentially all you need is a wearable device that tracks your distance and you run. You need a flat surface because anything hilly will, obviously, you won't run as far because it's more challenging. So you need like a flat surface, like a track field.

And you run for 12 minutes, and you pace yourself. You want to go hard, but you want to be able to, like, do it the entire time. And then there's an equation you can look up: 12-minute run test equation, VO2 max, and it's, you know, the distance.

And this whole equation will give you a really good estimate of your VO2 max for anyone that's interested in sort of seeing how their training affects their VO2 max. But I think one of the most convincing studies that I've seen for vigorous-intensity exercise has to do with structural changes in the aging heart. So as we age, our heart undergoes structural changes.

It gets smaller in size and it gets stiffer. And this translates to functional deficiencies, like exercise capacity goes down, but also it increases the risk for cardiovascular disease.

A lot of different changes start to happen in the cardiovascular system when that occurs. And so there was a study done at UT Southwest in Dallas by Ben Levine's group, where they took 50-year-olds that were. They were disease-free, but they were sedentary, right? So they didn't have type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease, but they weren't physically active.

And they put them on one or two different exercise protocols. One was the control group, which was more like a stretching, a little bit of bodyweight training. It wasn't high-intensity.

They weren't really getting the heart rate up a little more like a yoga-ish type of workout. And the other group did that, but they also had a high-intensity vigorous exercise workout program. And this was a two-year intervention study.

And so the first six months were like a progressive building up their endurance. And once they got to the six-month mark, most of these people were doing about four to five hours a week of training. And a good portion of that time was spent in what's called maximal…your maximal state exercise state, where they were doing like 20 to 30 minutes a day of maximal intensity exercise. Not maximal intensity, but steady state. So they were able to basically maintain the maximum amount of intensity they could for 20 or 30 minutes.

So it was vigorous. They were going 75, 80% max heart rate. They also did the Norwegian four-by-four protocol once a week.

And after those two years, the structural changes in their heart reverted back almost 20 years. So their hearts got more malleable, and they got smaller. Sorry, larger.

And it was like looking at a 30-year-old heart, and these were 50-year-olds. And so, I mean, to me, it was just so astounding that you could get structural changes in the heart. Essentially it's reversing the aging heart by just about 20 years from doing this vigorous-intensity exercise protocol in 50-year-olds that were sedentary.

And there's also blood pressure, I would say drug-size blood pressure, improvements with blood pressure with vigorous-intensity exercise. So there's been a variety of randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses of these trials that have found people that work out and do more vigorous-intensity exercise three to four days a week. About 20 to 60 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise can improve their blood pressure, similar to medications like antihypertensive medications.

And high blood pressure is not just a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. It's now been established that it's one of the most important early risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

So the fact that you can comparably get these improvements in blood pressure like you would get with a pharmaceutical drug is also, I think, extremely encouraging. Right?

Let's continue. So I want to shift gears just for a minute and get into some of the brain benefits.

We'll get to questions at the end. So I think probably one of the most convincing reasons to get your heart rate up high. When I say high, I mean 75, 80% max heart rate.

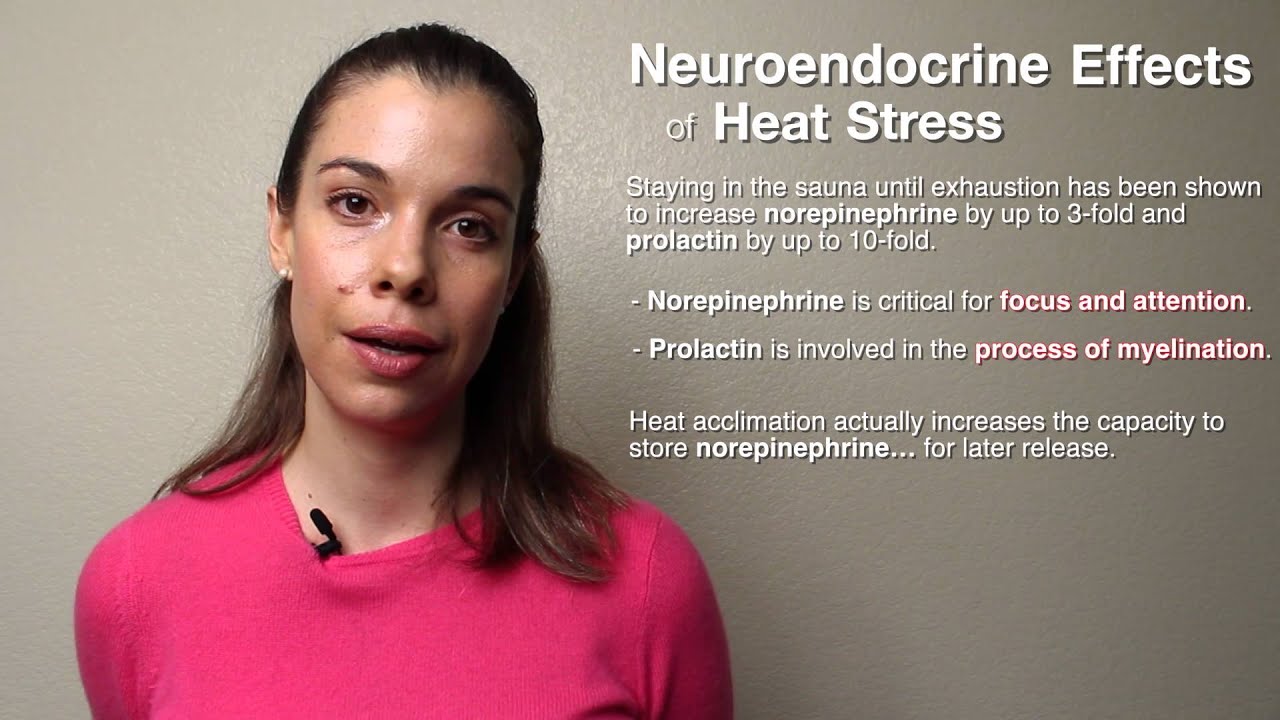

To do that is from brain benefits. And that largely has to do with something called lactate, which probably many of you are familiar with. So when you force your muscles to work so hard that you can't get oxygen to them fast enough to make energy, they have to adapt, and they use glucose as energy without the mitochondria, which is generally how you're making energy.

And as a byproduct of that, you're churning out lactate, which was thought to be this sort of metabolic byproduct. It turns out it's much more than that. And so lactate gets into circulation, and it's taken up by other tissues, including the muscle, the brain, the heart, liver.

And it's used as energy in those tissues. So it's a very energetically favorable source of energy. It's actually easier to make energy from lactate than from glucose.

So it takes less energy to make energy from lactate than glucose, but also it acts as a signaling molecule. It's a way for your muscles to communicate with other parts of your body because when you're exercising, it is a stress on the body. And so adaptations happen.

Right? When you're working your muscles hard, you can increase muscle hypertrophy. These adaptations happen. Cardiovascular improvements.

You're getting increases in stroke volume, cardiorespiratory fitness improvements. Well, the brain also works really hard during exercise. And so lactate is communicating with the brain.

And there's many benefits to having lactate go into the brain. And one of those is that it signals to the brain to make something called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. And what this is is a growth factor that is involved in increasing new neurons inside the hippocampus and other regions in the brain, but mostly the hippocampus, which is important for learning and memory.

And there's been intervention studies showing that aerobic exercise after older adults do it for two years increased their hippocampal volume by, like, 2%. So it increases neurogenesis. But it also is important for neuroplasticity.

This is the way your brain adapts and is able to adapt to the changing environment and still function. It plays a big role in depression. People that are depressed have a very low level of neuroplasticity, and so they have a hard time adapting to the changing environment, and that causes depressive symptoms.

So brain derived neurotrophic factor is, like, amazing for your brain. You want more of it, and high-intensity exercise is the way to get more of it.

Lactate also signals to the brain to make neurotransmitters like norepinephrine and serotonin. These studies have been done in humans. Lactate, again made from muscles. When you're forcing your muscles to work hard, when you're going high intensity, it crosses over the blood brain barrier, and your brain is working hard during exercise.

And so lactate is fueling that – your brain function during exercise, but it's also increasing things like norepinephrine, which is involved in focus and attention, serotonin. And there have been studies showing that even ten minutes of a high-intensity interval training workout can improve cognition, improve mood. I mean, it's just really easy to get those improvements in just a short amount of time by just getting after it pretty hard.

Some of the protocols that have shown improvements in maximizing BDNF really are intensity and duration dependent. So the harder you go, 80% max heart rate for 30 to 40 minutes is one of the most robust ways. There's also another really good protocol.

So this would be six minutes of high-intensity interval training where you do about 40-second all-out intervals separated by some recovery periods. That also has been shown to pretty robustly increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor as well.

So I just wanted to spend just a second talking about some of the anti-metastatic effects of a vigorous intensity exercise. Most of us here know that exercise is one of the best things you can do to prevent cancer, but also as an adjunct cancer treatment, many different ways that's occurring. But one interesting way that most people don't know about is through the shearing forces of your blood, just blood flow. So just getting that blood flow to go faster by exercising, by getting that exercise, kills what are called circulating tumor cells.

These are tumor cells that have escaped a primary site of the tumor, get into circulation, and they go and try to travel to other tissues and take camp there and metastasize. Well, circulating tumor cells are very sensitive to the mechanical forces, the shearing forces of blood flow, and they can't handle the stress like our normal cells can, and they die. And so I think that's a really interesting way to think about it, because it's like, oh, yeah, I need to get my blood flow up, I need to get my heart rate going and my blood flow up, and that is something that has an antimetastatic effect.

And there's studies that have shown, obviously, aerobic exercise, and the higher the intensity of the exercise, it can reduce the amount of circulating tumor cells in people with cancer, like colon cancer, circulating tumor cells in people with cancer, it's an indicator of bad outcomes. So they have a four times higher mortality risk than people without them. And people that engage in aerobic exercise have improved outcomes. They have better reduction in disease recurrence and also in mortality.

So I want to shift gears for a minute and talk about exercise snacks. So we're going to talk about improving metabolic health, but also longevity.

Exercise snacks – it's kind of a broader term, but it really can refer to either a deliberate sort of type of exercise that you do for one minute, two minutes, three minutes, and this is anything from burpees to squats. You can do high knees, you can do, you know, there's a variety of different things that you can do to get your heart rate up really high in a short period of time. And we're talking at least 75% max heart rate.

And there's studies showing that there's a real metabolic benefit to even doing a minute or two of this exercise snack type of exercise. And that, again, comes down to lactate.

Lactate – you're forcing your muscles to work really hard. Lactate gets into circulation, gets taken back up by the muscle, and it causes glucose transporters to come up to the muscle and sort of open the gates so that glucose can come in. And so this really improves blood glucose levels.

And there's been a lot of studies looking at this, particularly in people with type 2 diabetes, doing exercise snacks around mealtime. So anywhere between 30 minutes to an hour before or after a meal can really dramatically decrease the postprandial glucose response and improve blood glucose levels. Now, sure, that's important for people that are metabolically dysregulated, people with type 2 diabetes, but who doesn't want to improve their postprandial glucose response? I mean, that's part of what makes you feel sleepy and reduces mental clarity after a meal.

So timing these exercise snacks around meals is a great and sort of easy way to improve your blood glucose levels as well. And it's pretty easy to do. The other way it improves metabolic health is these exercise snacks, when you're doing a high-intensity interval training sort of thing, even one or two minutes, but mostly when you're going higher than that, like ten minutes, 20 minutes, it's a very potent stimulus to increase the number of mitochondria in your muscle tissue. Again, it's an adaptation. You are forcing your muscles to work so hard that they can't use their mitochondria, because, again, oxygen can't get there fast enough, and so they're forced to make energy another way.

But your muscle's smart, and it's like, oh, I need to adapt so that the next time I'm working hard, I can use my mitochondria. And the way it adapts is by making new mitochondria. It's called mitochondrial biogenesis.

And high-intensity interval training is one of the best ways to increase mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. Again, lactate plays a role in that, because lactate is that signaling molecule that increases a protein called PGC1-alpha that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis.

Exercise snacks have also been associated with improved longevity. So there's another type of exercise snack that's a little bit more of taking advantage of, like, everyday situations. It's called vigorous-intensity lifestyle. Sorry, vigorous, intermittent lifestyle activity.

And these types of exercises are like, let's say you work on the fourth floor of some office building. So rather than just walking up the stairs every day, which is better than taking the elevator, you sprint, or let's say you walk to your office. Well, rather than just walking, you interval walk, or you sprint there, you do some sort of interval where you're getting your heart rate up.

So there have been multiple studies showing that doing one to two minutes, of vigorous-intensity exercise, so people, these large studies, people are wearing wearable devices, and so researchers are getting their data, their heart rate data, and able to measure something and identify people that are getting their heart rate up right. And so people that do one to two minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise a day, sorry, three times a day, had about a 40% reduction in all-cause mortality. So that's dying from all non-accidental causes of death, and a 50% reduction in cardiovascular-related mortality, which is the number one killer in most developed nations.

So this is, again, just one to two minutes, three times a day, where you just – you're doing those exercise snacks. It adds up, it's beneficial, and clearly it's making an effect in people's lives.

And these benefits were also found in people that identified themselves as non-exercisers. In other words, they don't, like, go to the gym, they're not, you know, they're not taking time to, like, deliberately engage in a sort of exercise routine, and they still have these benefits. So how do you implement, you know, exercise snacks in your day? Why would you want to?

Well, there's evidence out there that just being sedentary. So, like, right now we're all sedentary where you're sitting – well, you guys are – yeah, you're sitting in your chair.

You've been in here for about, what, an hour or so. That is sedentary time. When you're sitting at your desk, at your computer for six hours or whatever, fill in the blank time, even though you're going to go to the gym later, or maybe you went earlier, that time that you're sitting is sedentary.

And being sedentary is an independent risk factor for cancer. So there is reason to kind of break up your sedentary time with exercise snacks. And again, these would be like a deliberate sort of thing that you can do.

So I think that maybe if we all just kind of stand up for a second and we're going to do high knees, because I feel like that's the easiest thing to do. Right? Like, there's enough space for that. Like, I don't think we can do burpees right here.

All right, actually, so to wrap this part of my talk up, all you need to do is some high knees, right? No. Yeah.

So finding something that you're going to do consistently that's really important, right? I'm talking a lot about vigorous exercise, but it needs to be something that you're going to do consistently.

Whatever it is. Norwegian four-by-four, if that's your thing, I'm definitely like: You're amazing.

So, you know, the thing is to really just measure your heart rate. Right. That's the easiest thing.

Make it consistent, do something you like. All right, we're going to shift gears just for a minute and talk a little bit about muscle preservation, the synergy of protein intake, lifting, resistance training, and heat exposure.

So peak muscle mass happens around between the ages of 20 and 30.

And then after that, as you start to get in your forties and fifties, you lose about 8% of muscle mass per decade. Once you get into your seventies, 15% of muscle mass per decade. So most people, by the time they're 70 or 80 years old, only have about 60% to 80% of the muscle mass they had when they were 30.

Skeletal muscle, is a reservoir for amino acids. So, like we store glucose as glycogen in our liver, in our muscle, we store fat as triglycerides. We don't really have a good way that we store amino acids, but we need amino acids every day.

Amino acids make up proteins, and proteins are doing everything in our body, from making neurotransmitters to making a heart beat, everything. So, unfortunately, if you don't get those amino acids from protein, you're going to pull from that amazing reservoir, your muscle, your skeletal muscle. And so you really need to be constantly giving yourself protein to not do that.

And so the question is, well, how much protein do you need to give yourself to not do that? And that's a pretty contentious, I would say, question that people have differing answers on. So the recommended daily allowance, the RDA was, this is set by these committees, and there's lots of things involved in that. But to simplify, about 40 years ago, this RDA was set and it was set to be 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram body weight. And that was thought to be the amount that you needed to take in every day to minimize the amino acid losses from muscle, right?

To replace all your amino acids to be able to get enough protein, right? Well, it turns out. So studies that have been done by experts like Dr. Stuart Phillips at McMaster University and others have shown.. So the way that RDA was 40 years ago set was, it was flawed in terms of the techniques that they used. They're called nitrogen balance studies. They underestimated the amino acid losses. And so here we are, 40 years later, scientists have more sensitive tools.

We have a lot more at our disposal, and they're saying, no, actually, we redid these studies and we found it's more like 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight as the bare minimum, to just basically be able to not be pulling amino acids from our muscle. Right?

And then that number goes up. If you're physically active, it goes up to 1.6 grams/kg of body weight. And then there's the elite level. You can go up even further than that. But I think the bottom line here is that the RDA is too low.

And there's a lot of scientific consensus in terms of people that are experts in that field that are saying, no, we need to boost that up. And another problem with that is that the RDA, 40 years ago, they did these nitrogen balance studies in young adults, not older adults. And we know that older adults, again, this is data from Stu Phillips lab – he's a real leader in this field – that older adults experience something called anabolic resistance. So their skeletal muscle is not as sensitive to amino acids to make… to increase skeletal muscle protein synthesis.

So he's done studies where he's found that actually older adults, they can prevent their atrophy by taking in 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram body weight versus the RDA, which is 0.8. So all the more reason to increase that RDA to 1.2 grams/kg body weight. Obviously, the less muscle mass you lose, the less frail you're going to be. And those studies have also been done.

More muscle mass, less frail, less likely to fall and break something, fracture risk and all that. So important to improve and increase that RDA.

Just as a quick aside, because we're talking about anabolic resistance, I just want to bring omega-3 in there. So Chris McGlory at Queen's University trained with Stu Phillips. And when he was training with Stu, he found that high dose omega-3, so anywhere between 4 to 5 grams could basically blunt the disuse atrophy that occurs by like 50%. And this was in younger adults, not in older adults, but it's just really…

So there's been some subsequent studies since then. This is really a growing field that's really in its infancy. But Chris and some other people believe that partly what's happening is omega-3s are sensitizing skeletal muscle to amino acids.

So this is independent of its anti inflammatory effects. And that's also, it's important to note here that the studies that they're doing, they preload people with high dose omega-3 for about one month, because it takes about one month for omega-3s to accumulate in cell membranes, including in your skeletal muscle, cell membranes. So that, I think, is also really an interesting thing. It's a growing field.

Like I said, there have been meta analyses looking at muscle mass in older adults taking omega-3 supplements. And if the doses are high enough, so at least 2 grams, so this is a meta-analysis of multiple randomized controlled trials. There is an improvement in muscle mass and also in some, there's some functional improvements as well, but the dose had to be at least 2 grams. For doses less than that, there was really no effect. Again, you'll find conflicting data in the literature, so it really depends on the protocol that's used. So we're talking about muscle mass, but strength actually fades faster with age.

So reductions in muscle strength can happen. So in men, they start to lose three to 4% in strength as they get older. Women are about 2.5% to 3%. And this can lead to functional issues, slow walking, you start to lose independence, you get increased fracture risk, frailty, and then all those things add up to a higher risk of death. So resistance training is one of the best ways to not only increase muscle mass, but also muscle strength.

And there have been a lot of meta-analyses of studies. So there's 21 different randomized controlled trials that were analyzed, and they found that older adults that engaged in resistance training one to three times a week for about eight to 18 weeks, could recover their strength that was basically lost over years of just being inactive.

So in other words, just doing eight weeks of resistance training, one to three days – one to three days – they could recover losses in strength from years of being inactive and sedentary. And strength is a lot easier for older adults to get those gains. They still can get gains in muscle mass as well, but the strength is something that's very encouraging as well, because the functional decline is something that's very important. And so if they can gain those strength, get those strength gains back, it's also going to improve their quality of life and also reduce their mortality risk.

So how much do you have to lift? Well, this is also very encouraging for older adults. Again, Stu Phillips pioneered these studies first in untrained individuals, where he showed that people could lift lighter weights and get the same gains in muscle mass and strength as people lifting heavier, as long as the volume was enough, as long as the effort was put in, and they're basically getting fatigued.

And then Brad Schoenfeld went on to show this also in trained people. So it wasn't just a newbie effect, and now it's, I think, becoming a little bit more clear that you don't have to lift heavy to get gains in muscle mass and muscle strength. You can lift lighter, as long as you're putting in that effort, and still get improvements in muscle mass and strength.

And I think that has a lot of relevance for a broader population of people, not just people that are really the elite sort of bodybuilder type. We're talking our parents, right, our grandparents, maybe people that don't really know how to do resistance training and don't want to injure themselves. So I think this has a lot of application, and it's a really important thing to point out.

Okay, for the last part of my talk, I just want to talk about deliberate heat exposure and how we're just going to focus on a couple parts of this. We're going to talk about how it can synergize with what we've been talking about today. Cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle mass.

So engaging in deliberate heat exposure from something like a sauna or even hot tub, hot bath, there's a lot of physiological adaptations and effects that happen that are very similar to aerobic exercise. And those things are like increased heart rate, you're getting increased plasma volume, you're getting increased stroke volume, you are getting hot. Your core body temperature is elevating, so you sweat to kind of cool yourself down.

There's a lot of similarities between deliberate heat exposure from the sauna and more like moderate intensity exercise. I would say your heart rate can go up to about 120 beats per minute. Some people can get it up a little bit higher, particularly if they go in right after a workout.

But there's been head to head comparisons of moderate intensity exercise and sauna use, and it's really like, the studies have shown they're pretty comparable. So, like, when you're doing the activity, heart rate goes up, your blood pressure goes up while you're doing the activity. But then after the activity, whether it's exercise or sauna, you're getting blood pressure improvements, your resting heart rate is improved, and these things are comparable.

So really, in some way, I would say, engaging in deliberate heat exposure from the sauna is mimicking moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. And there have been observational studies and some intervention studies we'll talk about in a second. But observational studies looking at people that are, and this is in Finland, where saunas are pretty ubiquitous and most people are using them.

So people in Finland that have sauna, are using sauna, and they exercise, have a better cardiorespiratory fitness than people that exercise alone. And we're talking about same volume of exercise. And these people, the ones that do that, but also sauna, had a better cardiorespiratory fitness than people that only engaged in exercise.

And then there's been intervention studies by Dr. Jari Laukkanen that have shown… So he's taken untrained people and put them on an exercise protocol it was a stationary bike. And then he had two groups, one that just did the stationary bike with passive recovery, and the other ones that did the stationary bike.

But then they went right into the sauna for 15 minutes, and he looked at a variety of parameters, one of them being VO2 max. So what he found was that those people that did the exercise bike and the sauna had a better VO2 max than the ones that only did the exercise bike. And to me, that makes sense, because, again, it's almost like extending the workout.

You're extending it just a little bit more. There were also better improvements in blood pressure and other lipid parameters as well in the group that also added a sauna plus the exercise. So I think there's benefits to deliberate heat exposure for people that are physically active, but also people that are not, people that are disabled, people that can't get on a bike, people that can't go for a run, people that can't do a burpee.

They can get into a sauna and get somewhat of that cardiovascular benefit. And there's all sorts of observational data out there looking at people that use the sauna four to seven times a week. They have a 50% lower cardiovascular-related mortality, 40% lower all cause mortality, and it goes on and on. So I think there's a lot of utility there for people that really just can't go and work out as well.

So another really important adaptation that happens when you are engaging in deliberate heat exposure for something like the sauna, also a hot bath, is the increase in something called heat shock proteins. And this is an adaptive response.

So as you're elevating your core body temperature, you're getting hotter. These heat shock proteins are activated, and they are the main role that they…the main function they serve is to prevent proteins from aggregating and forming plaques in your cardiovascular system, in your brain.

In fact, there's been multiple animal studies showing that if you give a mouse, like an amyloid-beta plaque, sort of what we get with humans and Alzheimer's disease, and you express the heat shock proteins, make them highly expressed, that they don't get the Alzheimer's like symptoms, and it helps with the plaque aggregates and stuff. So heat shock proteins play an important role in preventing protein aggregation. They have somewhat of an antioxidant effect.

They're also very important for slowing muscle atrophy. And this is, again, has to do with a variety of mechanisms. There's been a lot of animal studies on this, but there's now been some human data where people…there's intervention trials where they basically immobilize one of their limbs for a period of weeks and then did some local heat exposure, and the local heat exposure prevented the disuse atrophy by, like 40%.

So, you know, I think that's a very relative, again, a very relevant way for people that are injured, or, again, people that are older and they're experiencing a lot of muscle atrophy as well. But there was also a very recent study, and this is small, so it needs to be repeated, but people that were engaging in resistance training, either just alone or then went into the sauna right after the resistance training, they had greater gains in muscle mass if they went to the sauna right after resistance training compared to resistance training alone.

Well, actually, it was biomarkers of it, so they didn't directly measure muscle mass, it was biomarkers. But anyways, I think it's an encouraging and promising area that, of course, I'm excited about. I'm glad people are out there researching, but it's another possibility for a synergy between resistance training, between vigorous-intensity exercise, your exercise program, and then engaging in deliberate heat exposure as well.

So what are the parameters in a lot of these studies? Well, a lot of the parameters in many of these studies are coming out of Finland. The temperature is about 174 degrees Fahrenheit and the duration spent in the sauna is about 20 minutes. And that's important because people that spent less than 20 minutes, like, let's say they were in there for 11 minutes, they didn't have the robust effects.

So it really is a temperature dependent, duration dependent, but also frequency. So how many times a week people are getting in the sauna. For anything to occur, two times a week was like the minimum effective dose. So if people did something twice a week, it was more beneficial than once a week.

But people that did four times a week, four to seven, was really the most robust effects. So if you are looking for the most robust effect, the minimum time would be four times a week compared to one time a week. The humidity is usually around 10 to 20%.

And the question a lot of people ask is, what about what kind of sauna? What if you don't have a 175-degree sauna? What if you have an infrared sauna that goes up to 145? Can you get comparable effects? Again, temperature/duration dependent. So you're not going to get the same effect in 20 minutes in 145 degrees sauna, in terms of the heart rate and the cardiovascular adaptations, as you're going to get in 180 degree Fahrenheit sauna. Right.

So you might have to stay in there twice as long. You might have to stay in there 45 minutes to an hour to start to get your heart rate up. Again, you can wear some kind of heart wearable heart rate measurement device where you're looking at your heart rate and you can feel it, like when it starts to go up, sometimes it'll take a long time in an infrared sauna.

There are studies out there that have compared regular hot saunas to infrared in terms of cardiovascular benefits. And if the same volume of time is spent in there, you're not going to get as robust of an effect on blood pressure improvements as you would with a regular sauna. So again, you might have to spend more time in there as well.

Hot baths have also been shown to increase some of these biomarkers, like heat shock proteins that sauna has. And I really think that's a good…The fact that it's able to increase some of the same biomarkers to me signals that maybe hot baths or any sort of modality that's really increasing your heart rate that's making you hot is something that's going to be beneficial as well.

So I do think that people that don't have access to a sauna could do a hot bath. Get one of those little pool devices that measure temperature, put it in your bath and keep it up to 104 degrees Fahrenheit and be in there for 20 minutes, because that's what the studies have shown, 20 minutes at 104, shoulders submerged all the way down.

So that's it for today. Three powerful habits that I think will help delay the aging process that will improve health span. We have vigorous intensity exercise. Find a way to make it frequent. Do those exercise snacks, they're so easy. Incorporate resistance training protein intake. Thinking about that protein intake is a lot of work. And then engaging in deliberate heat exposure whichever way you like. I prefer to do it after a workout, but I also like to do it at night as well.

So that's what I have for you today. I hope you guys enjoyed it. And thank you so much.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Get email updates with the latest curated healthspan research

Support our work

Every other week premium members receive a special edition newsletter that summarizes all of the latest healthspan research.

Exercise News

- Omega-3s protect the heart and muscles against damage incurred during endurance running.

- Exercise improves depression through positive modulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

- Any Level of Physical Activity Tied to Better Later-Life Memory

- Lactate produced from high-intensity exercise may play crucial memory role and correlates closely with plasma BDNF.

- Urolithin A improves muscle strength, exercise performance, and biomarkers of mitochondrial health in a randomized trial in middle-aged adults