#45 Dr. Matthew Walker on Sleep for Enhancing Learning, Creativity, Immunity, and Glymphatic System

This episode is available in a convenient podcast format.

These episodes make great companion listening for a long drive.

The Omega-3 Supplementation Guide

A blueprint for choosing the right fish oil supplement — filled with specific recommendations, guidelines for interpreting testing data, and dosage protocols.

Matthew Walker, Ph.D., is a professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, and serves as the Director of the Center for Human Sleep Science. Formerly, Dr. Walker served as a professor of psychiatry at the Harvard Medical School.

Walker's research examines the impact of sleep on human health and disease. One area of interest focuses on identifying "vulnerability windows" during a person's life that make them more susceptible to amyloid-beta deposition from loss of slow wave sleep and, subsequently, Alzheimer's disease later in life.

Dr. Walker earned his undergraduate degree in neuroscience from the University of Nottingham, UK, and his Ph.D. in neurophysiology from the Medical Research Council, London, UK. He is the author of the New York Times best-selling book Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams.

Sleep as foundational bedrock for our ability to learn from experience

"You can't pull the all-nighter and hope to be able to continue to learn." - Matthew Walker, Ph.D. Click To Tweet

In some ways, the highly conserved nature of sleep across the animal kingdom seems like a paradox: Whereas closing our eyes to sleep obviously leaves us and the rest of the animal kingdom vulnerable for long stretches of the twenty-four-hour day, not sleeping must carry even more risk when we consider that it has not been weeded out in spite of this.

Without sufficient sleep, our ability to learn – the acquisition of new memories – begins to rapidly break down. And yet, this is only one of the major roles we now appreciate that sleep has. In this episode, sleep expert Dr. Matt Walker describes how sleep is critical to learning and survival because it facilitates a process he likens to the input, storage, and transfer of data in a computer.

Sleep preps the brain for information input

The formation, or "encoding," of memories occurs when the brain engages with new information – ideas, actions, or images – and leads to the formation of a representation of this information in the brain. Sleep preps the brain so that it can assimilate this new information and lay down the framework for new memory traces. Without sufficient sleep – in particular, the slow wave sleep that occurs during the stage of non-rapid eye movement, or NREM – the brain's ability to receive new input is markedly impaired. This phenomenon has critical implications in students and has been observed when college students who were deprived of sleep experienced dramatic deficits in their ability to learn new information.

Sleep facilitates information storage

Sleep also facilitates the more permanent storage of new information that has been stored in the hippocampus – the region of the brain responsible for the formation and consolidation of short-term memories. Sleep that occurs after exposure to new information fulfills the role of the brain's "save button."

Poor sleep, however, inhibits the brain's ability to form memories. Dr. Walker and his colleagues believe that this might be a quality of a time-limited capacity for hippocampal storage. Wakefulness that exceeds the typical 16-hour day might effectively outstrip this region's capacity for short-term storage of information.

Sleep provides a mechanism for information transfer and the formation of long-term memories

The intake and storage of mere short-term information are insufficient for optimal learning, however. The final, and perhaps most critical, way in which sleep aids in learning is that it provides a mechanism by which new information can be permanently stored – the formation of long-term memories via transfer to the brain's cortex, where they can be retained and then retrieved for future use. Without this transfer phase, we run the risk of hippocampal-associated memory impairment – a problem readily observed in older adults who experience loss of slow-wave sleep and subsequently demonstrate difficulty retaining memories overnight.

A fascinating new strategy to selectively enhance memories during sleep

When we sleep, memories and their associated events acquired during periods of wakefulness are reactivated. Essentially, the brain "replays" the events that occurred prior to sleeping, a process that stabilizes memories by serving as a pruning mechanism, selectively strengthening strongly associated memories and weakening weakly associated ones. A surprising fact is that this process can be amplified by "cueing" the reactivation during sleep with sub-awakening threshold sounds, odors, or other sensory cues – based on the context of the learning received the previous day.

A common thread between aging-associated loss of slow-wave sleep, accumulation of amyloid-beta, and impairment of hippocampal-dependent of memory

"If you look at how amyloid builds up in the brain, and if you look at the trajectory of Alzheimer's disease, it is a nonlinear exponential curve. It fits exactly what the sleep-dependent model of amyloid clearance would predict." - Matthew Walker, Ph.D. Click To Tweet

The decline of deep, slow wave sleep begins much earlier in life than most people would expect, with losses occurring as early as the late 20s. By the time a person reaches 50, they've lost roughly half of their deep sleep, and by the time they're 80, deep sleep brain waves are almost undetectable, according to Dr. Walker. Small wonder, then, that aging is accompanied by cognitive decline and substantive memory loss, especially in age-related disorders such as Alzheimer's disease.

Sleep disruption is integrally associated with Alzheimer's disease and its pathophysiology, with characteristic changes in sleep emerging well before the clinical onset of the disease. A key player in the development of Alzheimer's disease is amyloid-beta, a toxic protein that aggregates and forms plaques in the brain. Insufficient sleep increases the production of amyloid-beta, and amyloid-beta deposition, in turn, impairs sleep – in a vicious, self-perpetuating loop.

Recent studies indicate that the lion's share of amyloid-beta accumulates in the medial prefrontal cortex – an area Dr. Walker refers to as the "electrical epicenter" for the brain waves of deep, slow-wave sleep – and the severity of accumulation significantly predicts the degree and extent of cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer's. The accompanying loss of deep sleep impairs overnight memory consolidation and retention, further impairing hippocampal-dependent memory consolidation.

Dr. Walker's research suggests that quality of sleep in later life may actually confer a kind of resilience, staving off the cognitive decline commonly associated with aging.

Sleep facilitates the brain's self-cleaning mechanism: the glymphatic system

One of the reasons slow-wave sleep, in particular, seems to be so important is because it facilitates the proper functioning of the glymphatic system, a system crucial for clearing the brain of metabolites and other waste. The glymphatic system comprises a vast arrangement of interstitial fluid-filled cavities surrounding the small blood vessels that serve the brain. These perivascular structures are formed by astroglial cells and expedite the removal of proteins and metabolites from the central nervous system. During sleep, these interstitial spaces increase by more than 60 percent. This allows a "flushing" operation in which waste products can be more efficiently eliminated. The glymphatic system also facilitates the distribution of essential nutrients such as glucose, lipids, and amino acids, as well as other substances, such as growth factors and neuromodulators.

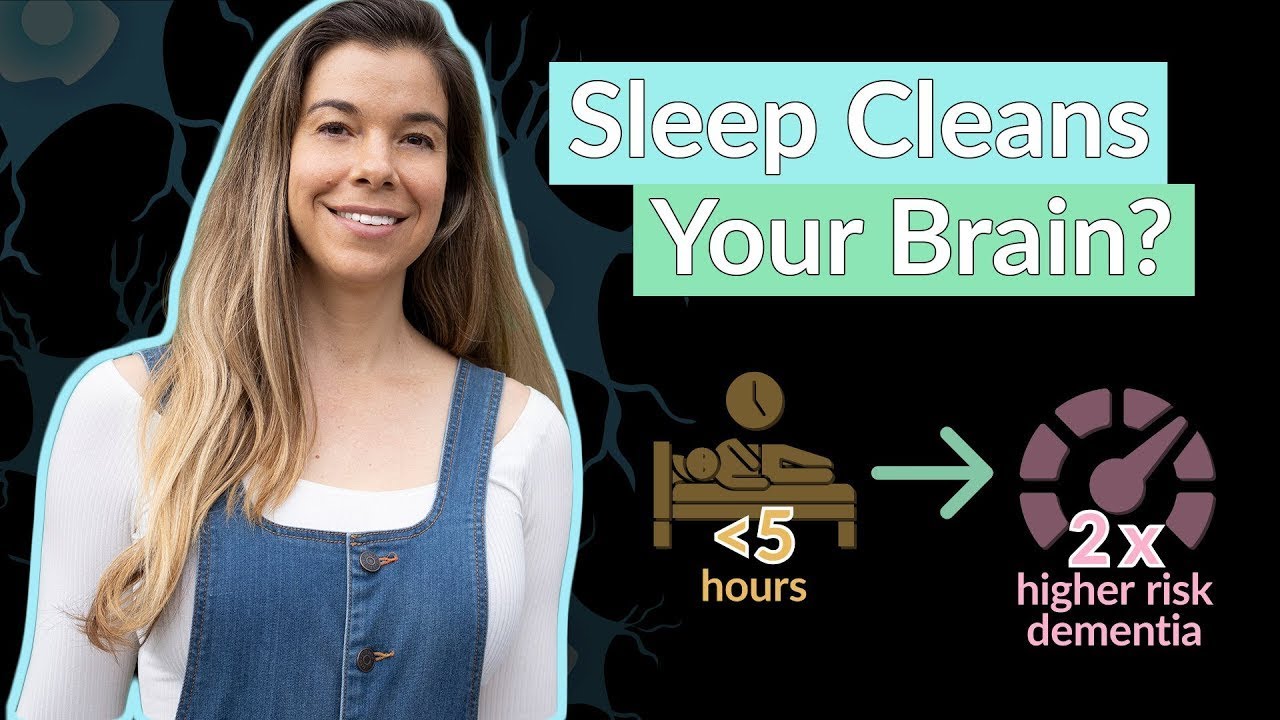

Our biological need for sleep may reflect a need for an essential downtime that enables the elimination of potentially neurotoxic waste products, including amyloid-beta, a toxic protein that aggregates and forms plaques in the brain. During deep, slow-wave sleep, the glymphatic system clears as much as 40 percent of the total amyloid-beta accumulation. A mere 36 hours of sleep deprivation, however, increases amyloid levels by 25 to 30 percent. This fascinating emerging story on a crucial function of sleep is just one more incremental discovery that helps us understand the existence of sleep in the midst of the evolutionary conundrum mentioned earlier. While many things may help us prevent the build-up of amyloid plaques by boosting our capacity for glymphatic clearance — such as exercise and adequate intake of omega-3 — by far, the most important factor is sufficient sleep, especially slow-wave sleep.

Much of this underscores the need for developing non-pharmacological strategies for addressing sleep loss or enhancement of slow-wave sleep. A strong candidate is transcranial direct current stimulation, a non-invasive, brain stimulation treatment that uses direct electrical currents to the brain to enhance deep sleep and improve memory capacity in older adults, and even doubling it in young adults. Other strategies involve auditory closed-loop stimulation – the delivery of tones in synchrony with endogenous slow-wave oscillations in the brain – and slow, rhythmic bed rocking.

Loneliness as a contagion promoted by sleep loss

"We have not been able to discover a single psychiatric condition in which sleep is normal."- Matthew Walker, Ph.D. Click To Tweet

Another, somewhat troubling, consequence of sleep deprivation is that it triggers the onset of a "loneliness phenotype." Lack of sleep induces critical changes within the brain, altering behavior and emotions, while also disturbing essential metabolic processes and influencing the expression of immune-related genes. The end result is that people who are sleep-deprived avoid social interaction. This asocial profile is recognizable by other people, who, in turn, shun the sleep-deprived people in a psychosocial loop that perpetuates in a vicious cycle of loneliness and other mental health disorders.

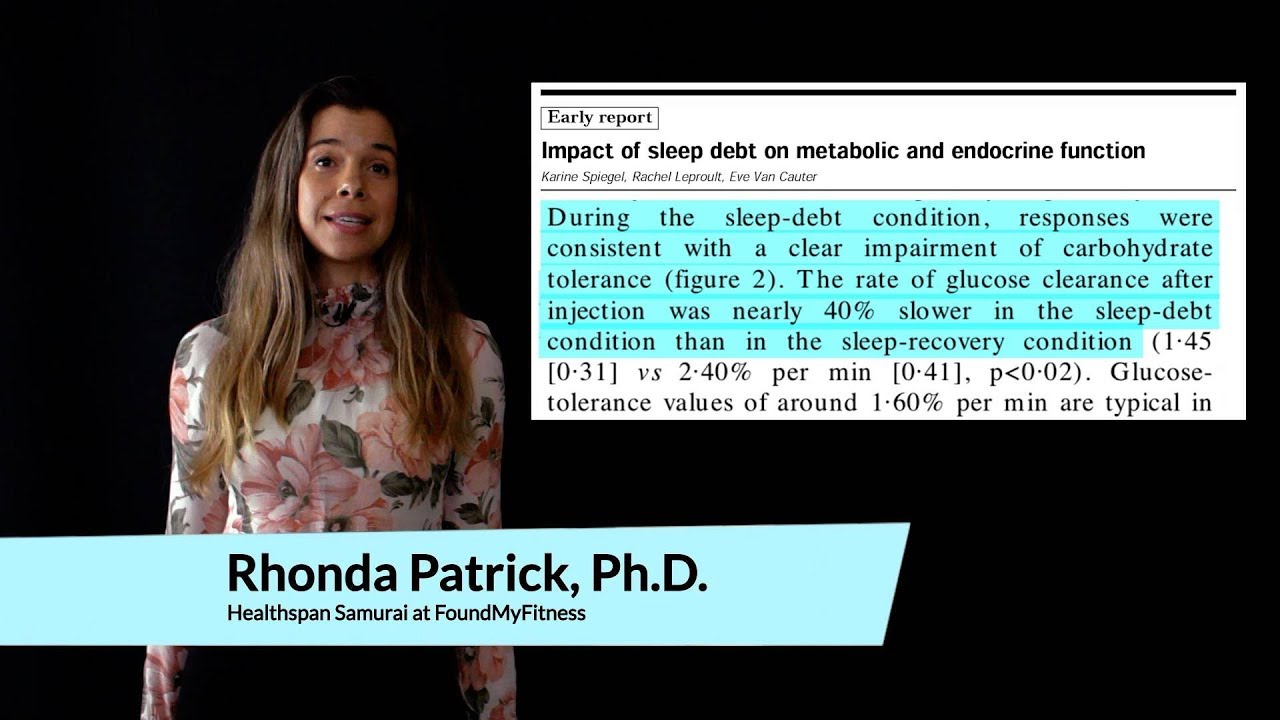

Impairment of glucose regulation and the promotion of an obesogenic profile

For anyone who habitually tracks their glucose levels, the importance of sleep can quickly become obvious. As Dr. Walker reveals in this episode, even a few days of impaired sleep, particularly loss of slow-wave sleep, manifests itself in a rather remarkable way: a change from potentially good glucose management, to something akin to a rapid onset of pre-diabetes. This is real-world observable.

In fact, sleeping less than seven hours per night has been associated with either having diabetes or eventually developing the condition. The problem is multifactorial. Not only does lost sleep cause our pancreatic beta islet cells that produce insulin to become less responsive to glucose signals, but muscle and other cells also become less responsive to insulin. These adverse changes from sleep loss are then compounded by deleterious alterations in the body's levels of appetite hormones leptin and ghrelin, which lead to, as Dr. Walker terms it, an obesogenic profile of energy consumption as a consequence of potentially chronic sleep loss.

Sleep plays a vital role in maintaining optimal mental and physical health throughout life. Listen to Dr. Walker explain how sleep is critical to our survival.

Learn more in Van Cauter et al. paper Metabolic consequences of sleep and sleep loss

Discussed in this episode…

-

How pulling an all-nighter decreases learning capacity by 40 percent. Study.

-

How sleep is important for long-term memory because during sleep, we shift memories from the hippocampus, the brain’s vulnerable, short-term storage reservoir, and we move them out to the cortex, the brain’s long-term storage site.

-

How sounds, when played at sub-awakening volume and coupled with certain learning can be used to contextually strengthen memories during sleep… a bizarre and fascinating phenomenon. Study.

-

On a similar note, how exposure to odors during learning and then again during sleep can create this exact same selective-enhancement of retention. That's right — smells and even sounds can reinforce memories even while we sleep. Study.

-

We also talk about a possible explanation as to why we do not remember dreams.

-

Dr. Walker's research showing how loneliness is a type of viral social contagion that is promoted by sleep loss, which was demonstrated by experiments that showed people who were sleep-deprived distanced themselves from social interactions, and were, in turn, shunned by other people. Study.

-

We discuss how the amygdala, the brain's emotional center, is 60 percent more reactive after sleep deprivation due to a dampening down of prefrontal cortex function. Study.

-

The effect that genetics plays in anxiety and poor sleep.

-

How the body's fight-or-flight mechanism is amplified in people who have insomnia.

-

The role of daylight during the day and darkness during the night in improving sleep and circadian rhythms and strategies for using this to our advantage.

-

The fascinating way heat can manipulate the production of crucial slow-wave sleep which has been demonstrated by changes as small as fractions of a degree.

-

How shorter sleep duration has been shown to reduce natural killer cell activity to 70 percent of normal, which, due to the function of natural killer T cells, really suggests chronic sleep deprivation may increase cancer risk. Study.

-

How people averaging less than six hours of sleep at night are four times more likely to become ill after being exposed to the flu virus. Study.

-

How poor sleep overall increases sickness rates, impairs glucose metabolism, and even decreases testosterone levels.

-

How people deprived of sleep for 36 hours show an increase in the amount of amyloid-beta found in their cerebrospinal fluid by as much as 25 to 30 percent and the crucial role that slow-wave sleep plays in helping us clear amyloid-beta. Study.

-

The importance of deep, slow-wave sleep, which begins to decline as early as our 20s, ultimately being cut in half by our 50s, and declining even more — to the point that it is almost undetectable by the time we're in our 80s, according to Dr. Walker. Study.

-

Some of the limitations of most sleep trackers when compared to polysomnography, the gold standard of sleep science diagnostic tools.

-

-

How people who sleep poorly tend to eat 200 to 300 calories more per sitting than those who sleep well and overall have more desire for caloric rich food — a phenomenon that, overall, tracks with a generalized pro-metabolic disorder quality that is associated with poor sleep and shorter sleep durations. Study 1; Study 2.

-

How certain dietary macronutrients may differentially affect sleep. Study.

-

How poor sleep disrupts the gut microbiome. Study.

-

How one cup of coffee in the evening can decrease deep sleep by about 20 percent — an amount that Dr. Walker suggests is equivalent to aging by 10 or 15 years.

-

How alcohol may have a short-lived sedative effect, it tends to fragment sleep, and suppresses REM sleep.

-

How Ambien-induced sleep resulted in a 50 percent loss in the learned connections made during the day in a specialized rodent test of neural plasticity, as well as some of Dr. Walker's other concerns about sleeping pill use in general. Study.

Check the timeline tab for an even more comprehensive breakdown of the discussion.

People mentioned

- Eve Van Cauter, Ph.D.

- Molly Crockett, Ph.D.

- Maiken Nedergaard, MD, DMSc

- Marcos Frank, Ph.D.

- Eus JW Van Someren, Ph.D.

- Aric A Prather, Ph.D.

- Peter Attia, M.D.

- Satchin Panda, Ph.D.

Learn more about Dr. Matt Walker

-

Sleep patterns change during human development, especially around age 12 months, when motor skill learning increases.

-

The strongest predictor of motor skill learning is the spike in stage 2 sleep and sleep spindles.

-

One of the key differences in human versus artificial learning is humans' integration and association of facts.

-

MRIs show that pulling an all-nighter decreases learning capacity by 40 percent. Study.

-

The impact of poor sleep on memory formation may be due to time-sensitive limited storage capacity of hippocampus and lack of non-REM sleep. Study.

-

Sleep is important for long-term memory because during sleep, we shift memories from the hippocampus, the vulnerable, short-term storage reservoir, and we move them out to the cortex, the long-term storage site within the brain.

-

MRI scans of rats learning spatial navigation show that their learning experiences replayed during the rats' sleep to create memories. Press release.

-

When sounds associated with specific objects are played during sleep, memory retention of those objects is better. Study.

-

Coupling sound with specific information enhances memory. NY Times article; Study.

-

Exposure to odors during learning and then again during sleep can enhance retention. Study.

-

Fear conditioning with a characteristic cherry-blossom odor was shown to be epigenetically heritable in mice. Press release; Study.

-

Walker theorizes about why non-REM precedes REM: to capture the memories in the cortex for associations and abstractions made during REM.

-

The connections made during REM sleep are the "longshots" of associations, where we find creative insight and solve large problems.

-

Walker gives examples of famous dream-inspired scientific and artistic insight.

-

People recall dreams more often if awakened during or shortly after dreaming.

-

Walker shares his theory about why we don't remember our dreams: they're stored but not readily accessible.

-

Loneliness as a type of viral social contagion promoted by sleep loss. Study.

-

When a person is lonely, their immune function shifts from mainly viral protection to mainly bacterial protection. Study.

-

In studies where animals are deprived of sleep, the animals become anxious, their cortisol increases, and their glucose metabolism is altered.

-

People who were sleep-deprived distanced themselves from social interactions, and were, in turn, shunned by other people. Study.

-

Sleep-deprivation-induced loneliness was contagious: after viewing people videos of people who were lonely, the viewers felt lonely, too. Study.

-

A small change in sleep can predict how lonely you feel the next day.

-

The amygdala, the brain's emotional center, is 60 percent more reactive after sleep deprivation due to loss of prefrontal cortex function. Study.

-

The unique way the effect of serotonin depletion has been characterized through an investigational technique known as acute tryptophan depletion. Relevant studies.

-

The similarity of the neural signature of sleep deprivation to that seen in psychiatric conditions and Dr. Walker's investigation into understanding the relationship between widespread sleep disruption in almost all major psychiatric conditions.

-

Genetics plays a role in anxiety and poor sleep.

-

The body's fight-or-flight mechanism is amplified in people who have insomnia.

-

Cortisol drops and heart rate slows during sleep in people with normal sleep patterns but not those with insomnia.

-

Walker talks about his personal decision to begin meditating to improve his sleep.

-

The importance of well-timed bright light exposure for the suppression of cortisol and maintenance of a strong circadian rhythm. Study.

-

The role of daylight during the day and darkness during the night in improving sleep and circadian rhythms.

-

Modern society's light exposure contributes to poor sleep, with too little light during the day and too much light in the evening.

-

Walker mentions the work of Dr. Satchin Panda. Episode.

-

Tip. Getting 30-40 minutes of bright light in the morning is crucial to establishing circadian rhythms.

-

Tip. Avoid wearing sunglasses in the early morning hours to reduce symptoms of jet lag.

-

Walker identifies strategies for minimizing light exposure at night to improve sleep, such as reducing blue-light (screen) time and turning off lights in the home.

-

People removed from the modern lighting environment slept better, longer, and earlier. Study.

-

Temperature as a powerful sleep trigger.

-

In order to fall asleep, the body's core temperature needs to drop by about 1°Celsius.

-

The San tribe in Namibia regulate their sleep according to thermal cues. National Geographic article.

-

If you lower core body temperature, you can increase non-REM sleep by 10-20 percent. Study.

-

When rats' paws are warm, they fall asleep quicker and stay asleep.

-

Saunas, hot baths, and hot showers induce vasodilation, which moves blood out of the body's core to dissipate heat, lowering core temperature and inducing sleep.

-

Walker mentions the work of Dr. Charles Raison. Episode.

-

The unique quality of certain immune molecules, such as IL-1, to be somnogenic, and the implications this might have for sleep and immune-modulating activities like exercise. Study.

-

When people are deprived of sleep, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels increase, which may have implications for hospital environment.

-

Shortening the amount of sleep people get reduces their natural killer cell activity by 70 percent, which increases cancer risk. Study.

-

The World Health Organization classifies nighttime shift work as a probable carcinogen. Study.

-

People averaging less than six hours of sleep at night are four times more likely to become ill after being exposed to the flu virus. Study

-

If you get only five or six hours of sleep at night, your immune response to a flu shot is cut in half. Study.

-

The unavoidable loss of sleep associated with pregnancy and being a parent, and some of Rhonda's personal experience with the effects, especially a decline in overall immune health and even glucose responsiveness.

-

Poor sleep increases sickness rates, impairs glucose metabolism, and decreases testosterone levels. Testosterone study.

-

Walker posits his theory about the role sleep deprivation plays as instigator of disease primarily through the manipulation of hormonal signals being governed by the autonomic nervous system.

-

How amyloid-beta tends to build up in the region that Dr. Walker identifies as the brain's “electrical epicenter,” critical in generating deep restorative sleep that is itself critical for amyloid clearance and — importantly — the learning and memory often lost to Alzheimer's disease. Study; Alzheimer's-sleep review.

-

How the newly discovered glymphatic system, which is responsible for ridding the brain of toxic metabolites during sleep, was found to be critically involved in the benefits of deep sleep with the cortical interstitial space increasing by more than 60 percent through a shrinking of glial cells, which allows cerebrospinal fluid circulating in the brain to better flush out toxic amyloid-beta protein. Study 1; Study 2.

-

When amyloid-beta protein builds up in the brain, sleep is impaired, which, in turn, impairs hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation and greater build up of amyloid-beta, creating a vicious cycle.

-

How people deprived of sleep for 36 hours show an increase in the amount of amyloid-beta found in their cerebrospinal by as much as 25 to 30 percent. Study.

-

People who are APOE4-positive are at double the risk of having sleep apnea. Study.

-

Sleep apnea reduces deep sleep and causes hypoxic damage to the brain. Study.

-

Some of Dr. Walker's current research focuses, including identifying "vulnerability windows" of sleep loss during a person's life that may make them more susceptible to amyloid-beta deposition later in life.

-

How deep sleep begins to decline during a person's 20s, and by the time a person is 50, they've lost 50 percent of their deep sleep; by the time they're 70, they've lost 95 percent of their slow wave sleep. Study.

-

Circadian rhythms change with age, blunting our bodily responses from signals that help us maintain biologically useful states such as wakefulness or sleepiness.

-

How, by modifying the light in an elderly care home to just increase the bright light during the day and, thus, improve circadian signals, patients experienced better mood and increased scores on activities of daily living and, in Alzheimer's patients, were able to improve an amount cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer's disease that was comparable in magnitude to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Study.

-

By modifying the light in a neonatal intensive care unit - especially through the introduction of a dark night cycle, premature infants showed better oxygen saturation, better tolerance to milk, and accelerated weight gain, which was reflected directly by shortened hospital stays. Study.

-

Some of the limitations of most sleep trackers when compared to polysomnography, the gold standard of sleep science diagnostic tools.

-

The unique place REM sleep may hold as a type of built-in emotional palliative care, even being predictive of remission from depression after trauma. Study.

-

The role REM sleep and NREM slow wave sleep together have in overall cardiovascular health by improving heart rate variability (HRV) and resetting what is known as the "baroflex threshold," respectively — essentially, performing a homeostatic recalibration of blood pressure.

-

Sleep is highly evolutionarily conserved across species in spite of obvious drawbacks, suggesting great biological importance.

-

If a person awakes before getting a full night's sleep, they should try to go back to sleep.

-

Walker identifies his four pillars of sleep: depth, duration, continuity, and regularity.

-

Night shift workers experience a degradation in the overall quality of their sleep, experiencing deficiencies in REM and deep NREM sleep, which suggests that, even for the same total time in bed, proper timing matters.

-

A person's individual chronotype – whether they're an owl or a lark – affects success in modern society, but is largely genetically determined.

-

The ratio of non-REM to REM changes throughout the night during sleep with the shift towards proportionately more REM sleep happening progressively towards the end, resulting in a more substantial loss of REM sleep when duration is cut short.

-

Sleeping at a time that is discordant with a person's chronotype can cause loss of REM sleep, which may help explain associative links between eveningness and depression, low mood, and anxiety.

-

Fighting one's chronotype may have increased risk for poor cardio-metabolic health that can be seen in biomarkers such as hemoglobin A1C, C-reactive protein, and more.

-

People who average less than seven hours of sleep are more likely to develop diabetes.

-

-

Poor sleep affects the release of appetite-regulating hormones leptin and ghrelin. Study.

-

-

Not only do people eat more after a bad night's sleep, they tend to eat more starchy or sugary foods.

-

A diet high in simple sugars and low in fiber makes it harder to fall asleep, and sleep tends to be more fragmented. Study.

-

Sleep or circadian disruption perturbs the gut microbiome, especially through the disruption of a delicate balance in the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes species making up the gut, in ways that have been associated with increased risk of metabolic disease and obesity. Study.

-

How it may be the ramping up of our body's fight or flight system from sleep deprivation or low quality sleep that induces some of the harmful changes in the microbiota, and how this two-way communication between the gut and the brain may also create an opportunity to use interventions that improve our microbiota to, in turn, improve our sleep.

-

Some of the pre-clinical evidence demonstrating that certain strains like Lactobacillis Rhamnosus have been shown to alter GABA activity in the brain, including regions like the hippocampus and amygdala, via a vagal nerve-dependent mechanism that ultimately suggests promise for conditions involving alterations in the GABAergic system like depression and anxiety. Study.

-

The extremely straightforward relationship sleep loss has on anxiety, where every hour past 14 to 15 hours of wakefulness results in an increase in anxiety in a dose-response sort of manner. Study.

-

Walker identifies some of his top actionable steps for improving what he calls the four pillars of sleep, which focus on improving depth, duration, continuity, and regularity. Continues at 02:17:45.

-

The evidence showing that reading from a light-emitting ebook reader or iPad may have a more significant blunting effect on melatonin than just reading a printed book with reflected light, leading to delaying of circadian phase, REM sleep propensity, and, ultimately, impaired morning alertness. Studies: 1, 2, 3.

-

Excessive smartphone use may also impair sleep through a more generalized promotion of anxiety. Study.

-

Matt's thoughts on the optimal temperature for sleeping (around 63 to 66 degrees).

-

A person shouldn't stay in bed if they can't sleep to reestablish the bed as a place of sleep.

-

One cup of coffee in the evening decreases deep sleep by about 20 percent - an amount that Matt suggests is equivalent to aging by 10 or 15 years.

-

Caffeine has a long duration of action.

-

Alcohol has a sedative effect, tends to fragment sleep, and suppresses REM sleep. Study.

-

Marijuana has variable effects on sleep, depending on the active components.

-

Sleeping pill use is associated with higher risk of cancer and all-cause mortality.

-

Ambien-induced sleep resulted in a 50 percent loss in the learned connections made during the day. Study.

-

Sleeping pill use was associated with a higher risk of death and susceptibility to infection. Study.

-

The American College of Physicians no longer recommends sleeping pills as a first line of therapy for insomnia.

-

Most medical doctors receive fewer than two hours of sleep education during medical school.

-

Walker has written a book called Why We Sleep.

-

Walker can be found on Twitter at @sleepdiplomat and on his website at sleepdiplomat.com.

Rhonda: Today's guest is Dr. Matthew Walker, author of New York Times best selling book Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, Professor of Neuroscience and Psychology at University of California Berkeley, and Director of the Center for Human Sleep Science.

YOU WILL NOTE… This episode starts sort of abruptly. The opening discussion is about HOW SLEEP PATTERNS CHANGE DURING HUMAN DEVELOPMENT, especially around age 12 months, when motor skill learning increases.

Matt and I had planned on doing an intro but the camera was rolling and the discussion was so interesting that we just kept going.

This is a good one, folks. Enjoy!

Matt: What's really interesting is if you look at sort of sleep, and we've done some of this work, and I maybe will speak about it on sleep and motor skill learning, and that seems to be more dependent on this sort of lighter form of non-REM sleep Stage 2 and particularly the burst of electrical activity the sleep spindles, there's a really bizarre bump in Stage 2 and sleep spindles during development, it happens right around the 12-month period, which is where, all of a sudden, you start to see considerable limb or multi-limb coordination. In other words, you start to perambulate, you start to learn how to walk.

It's almost as though there's like a homeostatic response, which is that with the drive for motor plasticity and learning comes a response from sleep to say, "Oh, now we're into motor skill learning? We need to consolidate." And you get this...it's a really strange bump, and it dies away again after the...

Rhonda: What's the sleep, the spindles, sleep two spindles, what stage is that?

Matt: Well, you see sleep spindles throughout almost all of non-REM. So once you get past the lightest sort of Stage 1 on REM, then you get spindles throughout all of non-REM, but they are a prototypical feature of Stage 2 non-REM as well. Then Stage 3 and 4, which is sort of like the deep sleep stuff, you also get spindles there, too. But in our hands, at least, the strongest sleep stage and the strongest electrical signature in your EEG that is predictive of your motor skill learning is Stage 2 and sleep spindles, both of which seem to have this bizarre sort of, you know, coincidental spike right around this developmental phase of crawling, standing, walking.

Rhonda: Yeah. So many things going on during the development. I mean, it's so fascinating to observe for sure.

Matt: And language, too. I mean, when we've looked at this as well with teaching adults foreign languages, or even actually just mathematical languages or artificial grammar, sleep is a huge component in that. But they also saw this fascinating thing with development, which was about not just concrete learning of individual facts but the generalization of knowledge.

So this is sort of the thing that I think separates us from computers, at least for now, which is that computers are very good at storing individual bytes of information in a vertical way very clearly. And we can do that, too, storing individual facts. But what computers don't do, which is what we do, is intelligently integrate and associate them together so that we can extract overarching patterns and schemas and statistical rules about this thing called the world in which we live.

And, yeah, sorry, I was just gonna say that you can, with infants, you can teach them just these novel sounds, and each one of these strings of sounds is unique and different. But there's something common about the grammar that is binding and overarching across all of them. There is an overarching schema that you could learn in addition to each one of the individual facts.

After they've had a nap versus an infant that has not had a nap, post-nap, the infants have extracted and understood the generalized rules of what they've been learning, not just the individual facts. Whereas infants that have learned but haven't napped have not sort of made the abstraction.

Rhonda: So my being a nap nazi, I should be rewarded for that, right?

Matt: Absolutely.

Rhonda: It's absolutely like...

Matt: And it stays from the, you know, infancy all the way through to adulthood. So if you're napping, I'm not gonna...well, there's a few double-edged sword aspects of napping.

Rhonda: So I wanted to ask you a question, you're talking about basically being able to connect the dots, you know, how would that sort of differentiates us from what a computer can do, I mean, one of the things. But is there a certain...I remember reading in your book, and this is probably the part of the book that I was more skimming, you know, like...and that was the importance of REM sleep and dreaming and creativity. So is that, connecting...because I feel like connecting the dots, you know, requires some creative thought to be able to kind of, like, put things together and come up with a big-picture idea and figure things out. So is it known? Is REM sleep important for that?

Matt: Yeah, it does seem to be. So if there is...So, I mean, we could take a step back and think about how does sleep achieve memory processing, learning, information processing. And sleep seems to be important in at least three ways. First, you need sleep before learning to actually get your brain ready to initially soak up new information, to initially lay down new memory traces.

But you also then need to sleep after learning to take those freshly-minted memories in the brain, particularly in a region that we call the hippocampus, which you could think of almost like the informational inbox of your brain, but it's very good at receiving those sort of new memory files. But you need sleep after learning to take those new memories and then essentially hit the save button on them so that you don't forget those informational pieces of the puzzle. So sleep before learning to get your brain ready, to acquire information. Sleep after learning to hold on to those individual facts.

Rhonda: So let me get this straight. So if you want, for example, short-term memory, right, because if you're sort of wanting to store things in the hippocampus, even short-term, that would be sleep before.

Matt: That's right.

Rhonda: And then if you want to then consolidate it and have a long-term memory, that would be your sleep after?

Matt: Sleep after.

Rhonda: Okay.

Matt: So you can't cheat sleep on either side of the memory equation. You've got to...You can't pull the all-nighter and hope to be able to continue to learn. And we did this study. We said sort of, you know, "Is it wise to pull the all-nighter before the exam?" So we took a group of individuals, assign them to one of two groups, a sleep group and a sleep deprivation group. A sleep group, they get a full eight hours of shut-eye that we measure here at the sleep center. The deprivation group we keep awake all night under full supervision. And they don't get any naps. There's no caffeine. It's miserable for everyone involved.

Rhonda: Wow. No caffeine.

Matt: No caffeine at all. And then the next day, we place them inside an MRI scanner, and we had them try and learn, and cram, essentially, a whole list of new facts into the brain, into the hippocampus. And the first result was that the sleep deprivation group was about 40% more deficient in their learning ability. So they learned 40% less, four zero, which is...

Rhonda: That's astronomical. That's a huge...

Matt: Non-trivial. I mean, if you want to put that in context, I guess it's the difference between acing an exam and failing at miserably 40%. What was interesting, though, is what was going on in the hippocampus, this informational inbox of the brain. When we looked at that in those people who'd had a full night of sleep, you saw lots of healthy learning-related activity. It was beautiful.

In the sleep deprivation group, we actually couldn't find any significant signal whatsoever. And so it was almost as though sleep deprivation had sort of shut-down-your-memory inbox and any new incoming files were being bounced. And we put forward a theory as to why that was. Perhaps that the hippocampus being a short-term reservoir of memory has a limited storage capacity, perhaps a little bit like a USB stick.

And you have maybe, in humans, a 16-hour recording capacity for information acquisition before you have to sleep. Because it's during sleep, then after learning. So that's sort of the story before learning. It's not great. We can show it. We know in the brain what part of the brain is failing to produce those impairments.

Rhonda: In that study, you were testing the ability to acquire new information.

Matt: Exactly, to sort of lay down those fresh memories and just to grab hold of them. And you can't do that well without sufficient sleep. And that seems to be in part related to your non-rapid-eye-movement sleep or your non-REM sleep.

But then, what we've also done in lots of these, and we and lots of other people have now replicated this finding, sleep after learning then takes those memories and it sort of it hits the save button on them. It's a little bit crass. Actually, what really happens is that during sleep, there is a file transfer mechanism that takes place at night, that we shift memories from that short-term vulnerable storage reservoir, the hippocampus, and we move them out to the long-term storage site within the brain, which is the cortex, which essentially acts like a hard drive.

And that means that when you wake up the next day, there are two delightful benefits. First, having shifted those memories from the short-term vulnerable reservoir to that more permanent sort of safe storage haven in the brain. They're protected, and they're safe, so that you're going to remember rather than forget.

The second benefit, however, is that sort of having cleared off those files from the hippocampus, almost like shifting files from the USB stick, you've cleared out all of that fresh memory encoding reservoir, so that when you wake up the next morning, you can start acquiring new files all over again. So it's this sort of elegant, symbiotic system of memory that happens.

Rhonda: Yeah, beautiful.

Matt: Yeah, absolutely. Sorry.

Rhonda: We'll, of course, use all this.

Matt: It's hermetically sealed. It's bizarre.

Rhonda: I remember reading somewhere that when you sleep, and this is related to what you were just talking about, that your brain sort of replays, like, electrical-activity-wise, it looks like you're literally, like, reliving the same thing you just learned or something. Is that...

Matt: That's absolutely correct. So these studies firstly happened in animals, and we've now been replicating some of them with brain imaging, with MRI scans in humans. Hard to believe, but we can do it. But the original findings were fascinating. They would place electrodes into that structure that we spoke about, the hippocampus, which also rats have as well, and it helps rats learn spatial navigation.

And they would place lots of electrodes into this part of the brain. And as the rat would run around the maze and learn the maze, individual cells would fire, and they would spatially code which part of the maze the rat was in. So different cells are mapping different parts. It's like sort of navigating a route from your home to work. Different sort of cells are coding the journey along the way.

Rhonda: Yeah. I'd probably would suck at doing that, but...

Matt: I think, yeah, yeah. I lost that. Yeah, some people say it's a male aspect of the gene, but I definitely lost it. Anyway, but what is delightful was that you could sort of hang, you know, a sound tone on each one of these electrodes. And what you would hear, and this is just, you know, for audio, you would hear sort of "buh buh buh bump, buh buh buh bump, buh buh buh bump," as the rat was running around the maze, as these cells were learning, encoding, and creating this kind of memory circuit essentially.

And, yeah, you know, "buh buh buh bump," off it goes. But what was genius is that they kept recording. And as the rat fell asleep, what did they hear? And it wasn't just static random firing, which is what we thought typically happens during sleep. In that static of electrical impulses at night, in a sea of electrical noise, came out a very clear, predictive, message, which was "brrrmp, brrrmp, brrrmp." It was exactly the same temporal sequence "buh buh buh bump, buh buh buh bump, buh buh buh bump," but it was sped up. And we now know that it's during sleep that we replay, but we replay at somewhere between 10 to 20 times the speed.

So it's as though you're kind of, you know, you've done the, you know, recording of whatever happened during the day, but then it gets replayed but at times 20 or times 10. "Brrrp, brrrp, brrrp, brrrp, brrrp."

Rhonda: Wow. So is this is a long-term potentiation part? Is this where it's solidifying?

Matt: Yeah.

Rhonda: Now what stage of sleep is that? I know you mentioned...

Matt: So that's during deep non-REM sleep.

Rhonda: Deep.

Matt: Yup, that we see that.

Rhonda: It's the sleep I'm always trying to optimize for, and it's just so difficult.

Matt: And it's difficult, you know, I think...Well, sleep in general is difficult for so many people, and we can speak why. So this starts to come back to your original question about REM sleep, though. So we get this memory replay. It's absolutely fascinating. We can now see it in humans. We can even manipulate it, which is amazing.

So if I teach you some information on a screen. Let's say it's about a particular object, like a fire engine, and you have to try and learn both the object and the spatial location of that on a screen. And then tomorrow, we're going to sort of come back. And I'm just going to show you the image and say, "Do you remember seeing it or not, yes or no?" And if you do remember seeing it, you've got to place where you thought it was on the screen. So you have to learn the item, and you have to learn the associated location.

But here's the great part. During the initial learning session, before you slept, not only do you see the fire engine but we play the sound of the fire engine, like a fire engine ring. And then we show you a kettle. It's whistling. We show you a cat. It's meowing. So each of these items that you're making has a contextual cue associated with it, a sound. And it's a congruent sound, fire engine sound, fire engine, kettle sound.

And here's the fun part. I can teach you a hundred of these items, and then during sleep, I'm going to replay those sounds that you heard as if I'm trying to get into your brain and I'm selectively reactivating each one of those individual memories. But I'm only going to reactivate and replay half of those memories. I'm gonna go to replay 50 of 100 things that you've learned.

And then the next day, we wake you up, and we test you. And firstly, your memory is better after sleep. And that's what we found. What's interesting is that for those items that I replayed during sleep, they are almost twice as superior in terms of your memory retention.

Rhonda: So the playing of them doesn't disrupt the sleep at all or...?

Matt: Well, that's the key. You have to play at a sub-threshold-awakening sound. So we will test your auditory threshold, and we will then play the sound at a level that we know is below your awakening threshold. So it's still just enough to get in to penetrate into the brain and tickle the memory and reactivate it...

Rhonda: That's fascinating.

Matt: ...but it's not enough to wake you up. So now, you know, you could imagine, you know, I've got these science fiction ideas of thinking, well, I learned all of this information, and maybe I can just put my favorite playlist on, you know, at night at low sound and, you know, stimulate these memories. Or could it be a study aid where you, you know, help students, like, sci-fi stuff?

Rhonda: So you think coupling different sounds maybe with, you know, learning facts, it may actually help...

Matt: Yeah.

Rhonda: Like irrespective of replaying them, like, during sleep, do you think just even the coupling of the sound somehow can help, can remember your...?

Matt: As long as those sounds have been coupled and bou to specific information. And this is what we call context-dependent or key-dependent memory. This is well known in psychology over about 100 years. If you study in the room that you're going to take the exam, you do better, because you actually use cues, contextual cues from around the room that are triggers to help you better remember.

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: We're just doing that with sleep.

Rhonda: What about caffeine? So if you study caffeinated and you don't take your exam caffeinated. Is this kind of the same concept?

Matt: We don't know about caffeine. It's an interesting thing. Caffeine may be a...it's a nonspecific stimulant, whether it works with ingested substances. We know, however, this works also with odors. So have you ever had that experience where you're sort of in an airport and you're sort of tying your shoelaces at the security, someone walks past with that cologne or a perfume of a person you knew, and it instantly unlocks that memory, as if the sound has triggered the reactivation of the memory, and it comes flooding back.

Well, you can do the same thing with this memory and sleep trick, where I teach you stuff during the day, and we can puff certain odors up your nose and associate the smell with the learning material. And then during sleep, you reperfuse the odor up the nose...

Rhonda: Oh, really?

Matt: ...and you can get the same benefit as well, the same doubling of the benefit.

Rhonda: Wow, that's fascinating. I remember this study that was done, that was coupling an odor, it was like a cherry blossom odor, with an electrical shock. So those, you know, classical fear studies that they do in mice, it was in rodents. And there was some sort of epigenetic change that the breathing of the odor, or the cherry blossom, was inducing. That was like changing some receptor on the glucocorticoid receptors. So it was getting passed on to, like, the next generation. And so even though the next generation didn't have the shock and the coupling of the smell, you know, if they were exposed to the smell, they have the fear.

Matt: The critical memory was translated from one generation to the next.

Rhonda: Yeah. So, anyways, it'd be fascinating. You don't know what role sleep plays in the epigenetic transfer.

Matt: Right. So if we all start doing this, you know, are our children going to be incredible memory replayers, you know, by the way of...But to come back to your...I'm sorry I've taken a desperately long time to answer your original question, which was what about REM sleep.

So what we've spoken about is the first two of the three stages of memory processing with sleep, sleep before to get the brain ready to lay down memories, sleep after to grab a hold of those individual memories and cement them into the neural architecture of the brain. Once you've done that, though, there's a final step. And that seemed to not depend on deep non-REM sleep but instead depend on rapid eye movement sleep or REM sleep, which is what most of us know as dream sleep.

And it's during dream sleep that your brain essentially performs informational alchemy, is what I would describe it as. It's a little bit like group therapy for memories that sleep has gathered in all of the information during the day. And during non-REM sleep, which always comes first, by the way, in our sleep cycle. We always have non-REM sleep first, then REM sleep second, then non-REM sleep again, then REM sleep second.

And we don't know why there is no good explanatory data suggesting why non-REM sleep always comes first and REM sleep comes second. But I've put forward the theory that, for information processing, it makes sense. Which is that non-REM sleep first to just get what you've learned and lock it into the brain. REM sleep then comes along, and REM sleep starts to fuse all of the information that you've recently learned with the entire back catalog of information that you've got stored up across a lifetime of experience.

And it's this sort of...Essentially, REM sleep is creating a revised mind wide web of associations. And I'd like to sort of think of what's going on with REM sleep. And we've done lots of these studies to look at this and these clever ways that you can look at sleep and associative memory processing and building new novel connections. And it's almost like memory pinball, where you take these new memories and you sort of launch them up, and you start bouncing them around into the architecture of information within the brain. And you're starting to test associations. You're starting to say, you know, "Should this new information be connected to this? Maybe not. Should it be connected to this? Maybe not."

Now some of that happens whilst were awake during the day. We make obvious connections. But what's strange is that we make connections during REM sleep but they're not of the same kind. The connections that we're making during REM sleep are the longshots. This is the bizarre...

Rhonda: The bizarre, right.

Matt: ...strange. You know, it's sort of...it would be the equivalent of saying, during the day, we take this information, and the connections we make are like a Google search gone right, which is the first page is all of the things that are most related. And it's very obvious. Page 1, that's directly related to what I inputted.

During REM sleep, it's almost as though you input the search term and you're immediately taken to page 20 of the Google search, which is about some field hockey game in Utah. And you think, I don't understand. Oh, that's interesting. I see what you're talking about. So we make these bizarre leaps of associative memory processing faith during REM sleep. And that's why we now understand that it's REM sleep that helps us divine remarkable creative insights into previously impenetrable problems.

And you can see this throughout the history of human beings, this dream-inspired insight, scientific demonstrations. You know, August Kekulé divined the idea of a benzene ring, these double carbon rings by dreaming of a serpent that swallowed its tail. Dmitri Mendeleev, you know, came up with the Periodic Table of Elements by way of dream inspiration. And, you know, people have won Nobel Prizes, Otto Loewi won the Nobel Prize for the demonstration of chemical transmission across nerve cells. And he dreamt of the experiment that helped improve that. He didn't dream of the concept itself, but he dreamt of the experiment to prove it.

Wonderful, artistic demonstrations of this, too. You know, Paul McCartney has written innumerable songs, it turns out, by way of his dreams. Keith Richards came up with the opening chords of Satisfaction by way of dream-inspired insight.

So REM sleep takes that third component of information processing. And I think it's what defines us differentially from computers in part, which is that deep sleep is about knowledge, which is gathering all of the information and holding on to it. REM sleep, I would argue, is about wisdom, which is knowing what it all means when you fit it together, you know. That's what I want from a good student. Don't just give me dry-book learning. Do you really understand it? Can you apply it? Are you creative? That's dream sleep.

Rhonda: Right, a deep thinker. Why do you sometimes not remember your dreams and sometimes you do remember your dreams? Do you have any idea?

Matt: Yeah. So some of it seems to be about, if you wake up out of that dream sleep period and then you go back into sleep, the awakening can sometimes help you commit that experience to memory.

Rhonda: Oh, okay.

Matt: But there are people who say that I never remember my dreams, you know. We can bring those people into my sleep center, and we can, you know, wake them up in the middle of dream sleep, and they'll say, "It's remarkable. For the first time, I was dreaming." And the answer is no. It's not the first time that you are dreaming. It's just the first time that you've actually remembered a dream, because it's the first time you've typically woken up.

Rhonda: Okay. My mother-in-law, you know, claims that she doesn't dream. And, of course, I'm like, "No, you have to dream."

Matt: Yeah.

Rhonda: That must be...

Matt: There are a selection of patients that have a lesion in a part of the prefrontal cortex, in their white matter, which are these big sort of informational fiber tracts that communicate impulses. If you get a lesion deep down there, we do seem to genuinely see a cessation of dreaming in those patients.

By the way, I would...I didn't even feel confident to write this in the book, and it's still a theory that I've never really heard in public, but go with me on this. Which is, I think that we may actually remember all of our dreams, or it's possible that there's a tenable theory. The problem is we don't have access to those dreams. Those dreams are memorized, and they are available. They're just not accessible. I think what happens as we wake up is that we lose the IP address to those memories. And the reason I believe this to be potentially true is have you ever had the experience where you wake up and you think, I was dreaming, and I know I was dreaming. And you try as hard as you can. The harder you try, the...

Rhonda: Yeah.

Matt: ...worse the memory-recall goes? And then you think, forget it. Two days later, you're walking along, and you see a street sign, and all of a sudden, it triggers the unlocking of that dream memory. You think, oh, that's what the dream was about.

As a neuroscientist, that tells me that the memory was present. The memory was available. The problem was accessibility. You couldn't gain recall access. So the information is there. It's just not accessible. If that's true...

Rhonda: It's happened to me just even after I've, you know, when I go to bed. You know, later that night, I hit the pillow, and all of a sudden, I remember the dream right as I'm hitting the pillow.

Matt: Right.

Rhonda: That's happened to me more than once. But you're right.

Matt: Right. It sort of tells you that there is...it's almost a scary prospect, which is that maybe every single one of our dreams throughout life are stored and are present and determine our behavior to some degree, because we know that there is an enormous amount of information that changes our behavior or decisions that goes on below the radar of consciousness, implicit memory. That could be true for dreaming, too.

And I think I've got an experiment that we may be able to design to actually get at this. And if that's true, it should, hopefully, radically change our view of dreaming, that dreams are ephemeral, that they dissolve quickly, they're forgotten, and they don't influence us as human species.

Rhonda: That would be pretty groundbreaking.

Matt: Yeah, we'll see.

Rhonda: You just had a study that I just read, I think, yesterday on sleep and it affecting behavior, loneliness, or...

Matt: Yeah, so we just published a sleep study demonstrating that sleep loss will trigger viral loneliness. And it was a three-part study. I mean, firstly, the reason that I got into this was loneliness is a killer. We know that there is a massive epidemic of loneliness now in industrialized nations. Being lonely increases your mortality risk by about 45%. In other words, being lonely is twice as risky for your death concern than obesity...

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: ...which is striking.

Rhonda: Yeah. There was actually a study showing loneliness changes, like, a massive amount of gene expression and, like, up-regulates NF-kappaB, cortisol, like all these pro-inflammatory genes. So it makes sense that it'd be associated with...

Matt: And what's bizarre about loneliness...By the way, I'm taking a complete...this has got nothing to do with sleep. But if you look at the profile of your gene expression and your immune system, you've got some immune components that will go after viruses. And viruses can only be transmitted from one human being to another by way of touch. They can't live outside of our bodies. Bacteria, so if you scrape yourself on a fence, like, you know, walking past it, you can get a bacterial infection because bacteria can live outside of the body.

When you become lonely, your gene expression shifts you away from a profile of immunity that normally deals with viruses and pushes you to more towards a bacterial defense profile.

Rhonda: Really?

Matt: Isn't that incredible?

Rhonda: Yeah, you should send me that study.

Matt: That your psychology...

Rhonda: Yeah, that's fascinating.

Matt: And there's a couple of folks at UCLA, who, if you ever have interest in this area of how loneliness, the mind, the mood...

Rhonda: Oh, totally. Yeah.

Matt: Okay, I've got to give you these people. I'm a complete fan of...

Rhonda: Please do.

Matt: ...their work. And they did this study. And it just blew my mind. How could a concept that is so sort of, you know, out there, and some people almost don't, you know, believe in loneliness. Toughen up. What's wrong with you? Go out make some...How could that change the expression of your genes and even alter how you, the organism, fend for yourself from an immunological perspective shifting you from viral to bacterial defense. But, anyway...

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: So coming back, I was desperately concerned about the state of loneliness. What's interesting, I was reading a lot at the time, because we do a lot of work with sleep and psychiatric disorders including anxiety, and when I was reading the studies where they would take animals and they would deprive them of sleep, you've got this anxiogenic profile where you got cortisol increasing, you got shift in insulin and glucose regulation, all of the bad things that you would not wish to happen, an anxiety increase, they had fear-like behavior all by way of just sleep restriction.

But what was also interesting is that sometimes the researchers would note, despite not measuring it systematically, that the animals, who would often be secluded by themselves in the cage, even when they were with other conspecifics, and other conspecifics would not approach them either.

Rhonda: Okay.

Matt: And so it seemed to me just from reading this, I thought, well, this seems like an animal phenotype of human loneliness. And it seems to be caused by a lack of sleep. So we decided we had to do the study.

So the first part of the study, we took a group of individuals, and they went through the study twice. They were either deprived of sleep for an entire night, or they got a full eight hours of sleep. The first test was, do you have a social repulsion boundary, and that boundary is increased when you are sleep-deprived. So I think everyone has that sense that if I start moving closer to you, you think, okay, do you know what, at some point, that's kind of enough. That's about my close distance.

What's interesting is that if I ask a sleep-deprived an individual to stay put, and I ask you, as an experimenter, to walk towards the sleep-deprived individual, and the individual says, "Stop," when they feel comfortable relative to when that very same individual has had a full eight-hour night of sleep. When you're sleep-deprived, you decide to push people a further distance away from you. So you have a lower desire for social proximity and social interaction.

Second, we then replicated that finding, but now we had them inside the MRI scanner. Because we wanted to see what was changing the brain to produce this social repulsion. What we found was that the regions of the brain that are essentially an alarm network, which is a sort of a stay-away-from-me network that is sort of in the parietal cortex and the premotor cortex, it's sort of what we call the near space network. So it creates your comfort of boundary. And when objects start to approach you, it alarms to say, "Incoming. Be cautious. Be wary." That part of the brain became hyperactive when people were sleep-deprived...

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: as if you were getting this repulsion signal from the brain. If that wasn't bad enough, the other parts of the brain that have been called the theory-of-mind network, which sort of helps you understand the intent of other people, it's a pro-social network in the brain, it cooperates pro-social interaction, that part of the brain was shut down by sleep deprivation. So it's a double-edged sort of sword.

So we weren't satisfied with that. Next, we wanted to say, "Could someone who just looked at these sleep-deprived individuals, could they actually judge them as being lonelier and looking lonelier and beaten, sort of perceived as lonely, even though they knew nothing about the experiment?"

So in the experiment with the sleep-deprived individuals, we also did videotaped interviews with them. And we just asked them general questions. Tell us about a movie that you watched? Or what was happening in the news this week? Just bland stuff. And then we got 1,000, I think was it was over 1,000 people, 1,083 people online. And they knew nothing about the experiment. They didn't know it's about sleep, sleep deprivation, knew nothing.

And we showed them just a 60-second clip of these people when they'd have a good night of sleep and when they were sleep-deprived. And we just asked them, "How lonely does this person appear to you?" And they knew nothing. But despite knowing nothing, they consistently and reliably rated the sleep-deprived version of the individual as seeming lonelier.

We also asked them, "Would you socially interact with this person? Would you friend them on Facebook? Would you work with them in a business environment?" And they consistently rated that they would prefer not to engage and interact with them.

Rhonda: Is that because they just looked unhappy or looked...?

Matt: Well, we actually think it's a collection of things. It's that their appearance, but also their vocal tone, is very different. We think there's a lot of...This is now one of the key things. What's communicating this asocial profile?

Rhonda: Oh, so they are listening to them speak?

Matt: So they watched them, and they listen to them speak. So they could hear them as well. So we demonstrated that. There was, unfortunately, the social repulsion on both sides of the equation. When you're sleep-deprived, you yourself don't want to have anything to do with other people. And that perhaps wouldn't be so bad if people would only at least come to your rescue, because they would see you in need. The opposite is true. People find you socially repulsive as a consequence. So there's a push from both sides of the social dyad.

The next thing, we asked those people who were rating the sleep-deprived individuals, we also said, "Look, how lonely do you feel after just the 60-second clip?" And they themselves felt lonelier after interacting with sleep-deprived individuals. In other words, this contagion of sleep-deprivation-induced loneliness.

Rhonda: So I wonder how much of this can be translated to, like, someone that, say, for example, gets only five or six hours of sleep versus, of course, not getting a full night sleep. You know, maybe there's, like, a little, just a little bit of this penetrating...

Matt: We then asked that question. That was the final part of the study, which is that we said, "Okay, this is extreme sleep deprivation, and most of the population does not undergo this. What about a more ecological version?" So we tracked hundreds of people across two nights of sleep. And we asked, just by a subtle variation of nature, our small perturbations of sleep from one night to the next, do they predict how lonely you experience yourself to be from one day to the next? And these are small minute changes in sleep efficiency, just small reductions in sleep of tens of minutes.

Lo and behold, even just that small change in your sleep from one night to the next, we could measure, predicted how lonely you would experience life the next day from one day to the next. So it doesn't even take, you know, two hours of sleep reduction.

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: Small minutes.

Rhonda: I remember reading somewhere, too, that isn't the, like, amygdala, like hyperactive or something happens, there's not an inhibitory signal that occurs if you're sleep-deprived or...?

Matt: That's right.

Rhonda: Is that correct?

Matt: Yes.

Rhonda: So then you're feeling more...you're, like, alarmed and, you know, just anxious and feeling that in a, say, threat...

Matt: That's right.

Rhonda: ...that ongoing threat that really isn't there.

Matt: Exactly, yeah. So we published the study in 2007 where we, again, sort of sleep-deprived people, put them inside an MRI scanner, and we showed them increasingly negative and aversive and unpleasant images. And what we saw is that, relative to people who'd got a full night of sleep, the amygdala, this sort of emotional epicenter for the generation of strong, emotional, impulsive reactions, that deep emotional center was 60% more reactive under conditions of a lack of sleep.

And then we asked why. Why is your emotional brain so sort of sensitive and erupting with such extraordinary activity? And what we then went to find, or went on to find out in later work, was that another part of your brain called the prefrontal cortex that sits directly above your eyes here, and particularly the middle part right between your eyes, that part of the brain acts almost like the CEO of the brain, of your emotions, and your hedonic impulses. And it sends sort of an inhibitory top-down regulatory control. It's sort of, like, the brakes on the gas pedal of your emotions.

That part of the brain was shut down by sleep deprivation, and you'd lost that communication to the amygdala. So now you, from an emotional standpoint, you were all emotional gas pedal and too little regulatory control brake as it were.

Rhonda: It's really interesting. This work kind of reminds me of...I'm not sure if you're aware of any of this research. A lot of it has been done by Dr. Molly Crockett, who, I believe, now she's at Harvard. But she has done a lot of studies looking at serotonin depletion in the brain. And basically, you can induce that by giving acute tryptophan depletion, giving someone like branched-chain amino acids to compete with transport for tryptophan in the brain, which then basically drops serotonin levels. I mean, you can drop your serotonin levels down to, like, 10%.

Matt: And mood is...

Rhonda: And the same thing happens where, exactly what you were describing, the inhibitory signal that happens from the prefrontal cortex onto the amygdala is, like, stops. And so people become extremely impulsive. Terrible moods, a little more aggressive, their long-term planning shuts down, and they just, like, going for the short-term gratification. Very similar. So it'd be kind of interesting...I don't know how serotonin would be related to all that, but there must be some sort of connection.

Matt: Yeah. I mean, and I think there's a number of different, I think, neuro chemicals that can produce that same kind of neural phenotype and as it were. But what struck me was that when I looked at that neural signature of sleep deprivation for the emotional brain, it was not dissimilar to numerous psychiatric conditions. And that then now, gosh, 11 years ago, I'm showing my age, but that set sort of, you know, the sleep center off on a completely new trajectory of work. And we're doing a lot of this work in sleep and psychiatric disorders.

And I think one of the most fundamental things that I can say at this point is that we have not been able to discover a single psychiatric condition in which sleep is normal. And so I think sleep has a profound story to tell in our understanding, maybe our treatment, I don't know about prevention, but possibly, of grave mental illness. And psychiatry has known this, by the way, for, you know, 40 or 50 years. It's always been documented that sleep disturbance goes hand-in-hand with psychiatric disturbance.

Rhonda: Maybe there's some sort of complex gene environment interaction. A few people that are more genetically susceptible and are getting...losing the sleep, or, like, the ones that are kind of pushed into a disease state.

Matt: And we've seen this, too, that if you look at that emotional brain reaction signature that I just sort of described, and you repeat that, but with people who are high-anxious and low-anxious, and we know some of the genes that are associated with being high-anxious and low-anxious. So we're using anxiety as a sort of a proxy for perhaps a particular genotype here. What you see is that it's those high-anxious people who are the most vulnerable to this impact of a lack of sleep. Those who are low-anxious still have a bad outcome, but it's nowhere near as bad. So there seems to be sort of interactions here between sleep loss and your basic trait levels of being sort of a nervous, anxious type to begin with.

Rhonda: That makes sense.

Matt: And those are the people who are, sadly, the people who typically don't get a good night of sleep anyway.

Rhonda: Right. So you're saying anxiety is, like, one of the things that stops me from sleeping.

Matt: It's the principal trigger of insomnia.

Rhonda: Yeah, really, true.

Matt: It's the model of insomnia right now, is that you get...And if you look at the nervous system, that's how we understand insomnia right now, is that its principle is...I think ultimately we'll find that there are multiple flavors of insomnia, different forms. We already categorized two of them. We've got what we call sleep onset insomnia and sleep maintenance insomnia, difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep. They're not mutually exclusive. You can have both, or you can just have one or the other.

But coming back to it, I think the overarching biological red thread narrative of insomnia is an amplified fight-or-flight nervous system, that your nervous system is split into these two branches, what we call sort of the sympathetic and parasympathetic parts of your autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic is anything but sympathetic. It's poorly named. It's the fight-or-flight branch of your nervous system. It ramps you up, charges you up, releases cortisol, adrenaline.

You constantly see an overactive, sympathetic nervous system in people with insomnia. And when you measure their cortisol across the 24-hour period, in most of us, just as we're getting to our natural bedtime, cortisol just starts to now drop down. We start to see that cycling down of cortisol. The opposite happens in people with insomnia. You get a continued rise right around that bedroom period. And it seems to be very predictive of sleep onset problems.

If you look throughout the night, cortisol then starts to plummet, and it drops beautifully down. It's part of the reason why deep sleep is the best form of natural blood pressure medication that you could ever wish for. Your heart rate drops down, your vessels relax, cortisol drops down. But in other insomnia patients, we see this bizarre spike in cortisol in the middle of the night. And it predicts nighttime awakenings. It predicts sleep maintenance insomnia.

Rhonda: I have experienced...So that's one of the problems that I actually have. It's much, much better now that my stress level is, like, maintained. At graduate school, I would get nighttime awakenings where my heart would start racing. And I would wake up thinking that there was a spider or some kind of threat. And I would scream, and sometimes fly out the bed. I mean, you know, and just...it would scare my husband, you know. At the time, we weren't married. But, I mean, you know, these nighttime awakenings, it was something that's dated back for quite some time. But really, it manifested during a very stressful period, and that was graduate school.

Matt: We see that...

Rhonda: Got much better.

Matt: ...so frequently.

Rhonda: Yeah.

Matt: But if you can think about that as sort of, you know, a stress management component to insomnia, you know, it's part of what we call cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, which is sort of dealing with that stress, you know, meditation. There's great apps out there, like Headspace, for example.

And the data on meditation and insomnia is very very powerful. You know, I'd known about it a little bit, but I hadn't read really all of the studies until I started researching it for the book. And I was so convinced that I started meditating. And I haven't stopped since. Because it was, you know...Typically, I'm not a bad sleeper. I'm a light sleeper. I'm a pretty good sleeper. I found it hugely useful for times when I was under stress, or when I was traveling and jetlag. It's very beneficial, too.

But that underlying theme, I think, as a message for insomnia, it's not the only cause of insomnia, but it seems to be if there's one common sort of rule that binds many of the patients with insomnia together, it's this overactive fight-or-flight branch of the nervous system. And if you can settle that down, you are certainly on the path towards better sleep.

Rhonda: Right. And to kind of just...Another point that you made talking about, you know, the hormonal response and the cortisol rising typically when it's supposed to be falling, that kind of prevents you from falling asleep, there is some interesting research that I've read where, and I know you and I have talked about how the importance of bright light exposure...Bright light exposure for six hours a day...I mean, no one does that nowadays. We're always inside. So it's rare unless you're, like, working out in a nature park or something.

Matt: The irony of these things...

Rhonda: Right, you know.

Matt: Yeah. It's for the camera. I promise.

Rhonda: Right. But, actually, it was shown to lower cortisol by 25%.

Matt: Yup.

Rhonda: So this is, like, you know, another kind of I don't know if that would even help someone with the anxiety or, you know...

Matt: No, I think it's...there's no studies testing it yet, but there are studies...So just sort of to go back to make this point, we normally have a circadian rhythm, this beautiful sort of 24-hour rhythm. And we human beings were diurnal, and we like to sleep at night, be awake during the day. We have this awesome upswing of our circadian rhythm sort of once we wake up sort of 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. It starts to peak during the day. It drops down a little bit in the mid-afternoon. And that's why you sort of get around meeting tables in the middle of the afternoon these sort of, you know, head nods. It's not people listening to a good music. It's like, actually, it's a pre-programmed dip in your alertness. And then it rises back up, and then it drops down at night.