How sound and smell are tied to learning, and the connection to sleep | Matthew Walker

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The BDNF Protocol Guide

An essential checklist for cognitive longevity — filled with specific exercise, heat stress, and omega-3 protocols for boosting BDNF. Enter your email, and we'll deliver it straight to your inbox.

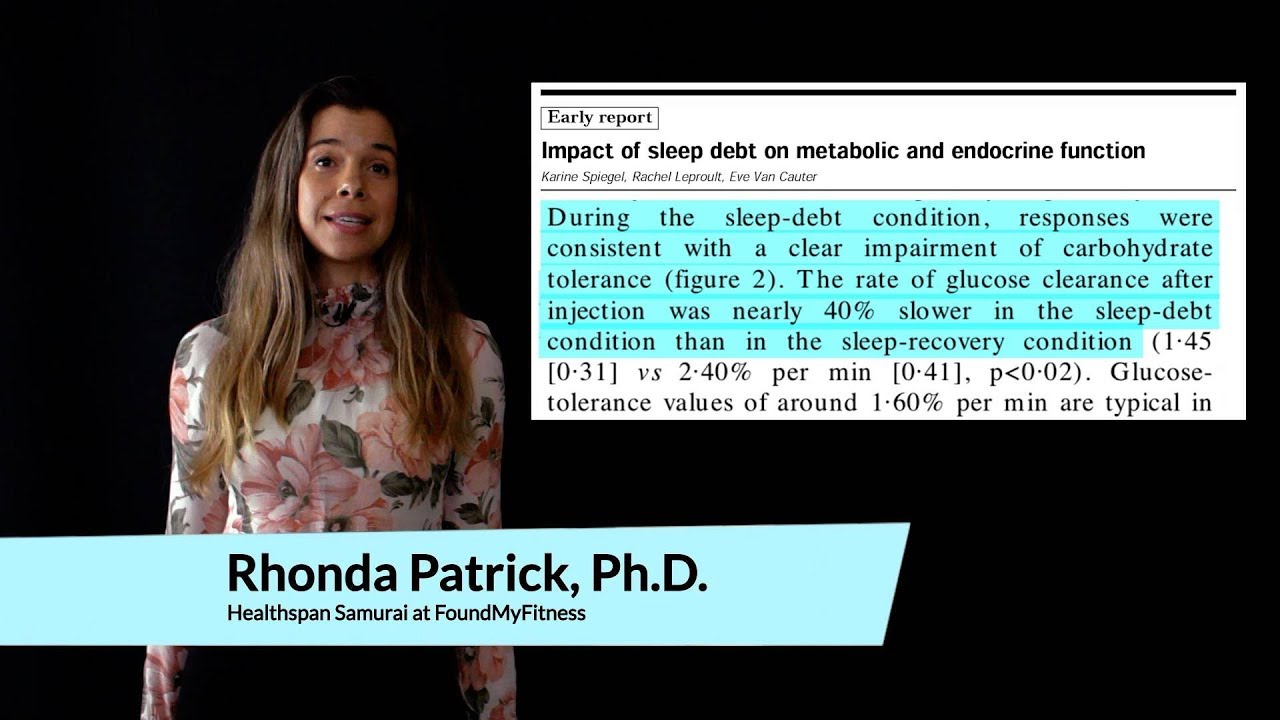

Context-dependent memory, a type of memory that occurs when contextual cues facilitate memory recall, is based on the premise that during memory storage, contextual information, such as sounds, smells, or tastes, are also stored. Retrieval of the memories is enhanced when exposed to the context. Although smells are among the strongest cues in inducing and retrieving memories, sounds can also provide strong stimuli for learning. In this clip, Dr. Matthew Walker describes how sound and smell cues played during learning and subsequent sleep can enhance memory formation and retrieval.

Matt: So this starts to come back to your original question about REM sleep, though. So we get this memory replay. It's absolutely fascinating. We can now see it in humans. We can even manipulate it, which is amazing.

So if I teach you some information on a screen. Let's say it's about a particular object, like a fire engine, and you have to try and learn both the object and the spatial location of that on a screen. And then tomorrow, we're going to sort of come back. And I'm just going to show you the image and say, "Do you remember seeing it or not, yes or no?" And if you do remember seeing it, you've got to place where you thought it was on the screen. So you have to learn the item, and you have to learn the associated location.

But here's the great part. During the initial learning session, before you slept, not only do you see the fire engine but we play the sound of the fire engine, like a fire engine ring. And then we show you a kettle. It's whistling. We show you a cat. It's meowing. So each of these items that you're making has a contextual cue associated with it, a sound. And it's a congruent sound, fire engine sound, fire engine, kettle sound.

And here's the fun part. I can teach you a hundred of these items, and then during sleep, I'm going to replay those sounds that you heard as if I'm trying to get into your brain and I'm selectively reactivating each one of those individual memories. But I'm only going to reactivate and replay half of those memories. I'm gonna go to replay 50 of 100 things that you've learned.

And then the next day, we wake you up, and we test you. And firstly, your memory is better after sleep. And that's what we found. What's interesting is that for those items that I replayed during sleep, they are almost twice as superior in terms of your memory retention.

Rhonda: So the playing of them doesn't disrupt the sleep at all or...?

Matt: Well, that's the key. You have to play at a sub-threshold-awakening sound. So we will test your auditory threshold, and we will then play the sound at a level that we know is below your awakening threshold. So it's still just enough to get in to penetrate into the brain and tickle the memory and reactivate it...

Rhonda: That's fascinating.

Matt: ...but it's not enough to wake you up. So now, you know, you could imagine, you know, I've got these science fiction ideas of thinking, well, I learned all of this information, and maybe I can just put my favorite playlist on, you know, at night at low sound and, you know, stimulate these memories. Or could it be a study aid where you, you know, help students, like, sci-fi stuff?

Rhonda: So you think coupling different sounds maybe with, you know, learning facts, it may actually help...

Matt: Yeah.

Rhonda: Like irrespective of replaying them, like, during sleep, do you think just even the coupling of the sound somehow can help, can remember your...?

Matt: As long as those sounds have been coupled and bound to specific information. And this is what we call context-dependent or key-dependent memory. This is well known in psychology over about 100 years. If you study in the room that you're going to take the exam, you do better, because you actually use cues, contextual cues from around the room that are triggers to help you better remember.

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: We're just doing that with sleep.

Rhonda: What about caffeine? So if you study caffeinated and you don't take your exam caffeinated. Is this kind of the same concept?

Matt: We don't know about caffeine. It's an interesting thing. Caffeine may be a...it's a nonspecific stimulant, whether it works with ingested substances. We know, however, this works also with odors. So have you ever had that experience where you're sort of in an airport and you're sort of tying your shoelaces at the security, someone walks past with that cologne or a perfume of a person you knew, and it instantly unlocks that memory, as if the sound has triggered the reactivation of the memory, and it comes flooding back.

Well, you can do the same thing with this memory and sleep trick, where I teach you stuff during the day, and we can puff certain odors up your nose and associate the smell with the learning material. And then during sleep, you reperfuse the odor up the nose...

Rhonda: Oh, really?

Matt: ...and you can get the same benefit as well, the same doubling of the benefit.

Rhonda: Wow, that's fascinating. I remember this study that was done, that was coupling an odor, it was like a cherry blossom odor, with an electrical shock. So those, you know, classical fear studies that they do in mice, it was in rodents. And there was some sort of epigenetic change that the breathing of the odor, or the cherry blossom, was inducing. That was like changing some receptor on the glucocorticoid receptors. So it was getting passed on to, like, the next generation. And so even though the next generation didn't have the shock and the coupling of the smell, you know, if they were exposed to the smell, they have the fear.

Matt: The critical memory was translated from one generation to the next.

Rhonda: Yeah. So, anyways, it'd be fascinating. You don't know what role sleep plays in the epigenetic transfer.

Matt: Right. So if we all start doing this, you know, are our children going to be incredible memory replayers?

A type of memory that occurs when contextual cues facilitate memory recall. CDM is based on the premise that during memory storage, contextual information, such as smells, tastes, or sounds, are also stored. Retrieval of the memories is enhanced when exposed to the context. Olfactory (smell) stimuli are among the strongest cues in inducing and retrieving memories.

Genetic control elicited by factors other than modification of the genetic code found in the sequence of DNA. Epigenetic changes determine which genes are being expressed, which in turn may influence disease risk. Some epigenetic changes are heritable.

A distinct phase of sleep characterized by eye movements similar to those of wakefulness. REM sleep occurs 70 to 90 minutes after a person first falls asleep. It comprises approximately 20 to 25 percent of a person’s total sleep time and may occur several times throughout a night’s sleep. REM is thought to be involved in the process of storing memories, learning, and balancing mood. Dreams occur during REM sleep.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Hear new content from Rhonda on The Aliquot, our member's only podcast

Listen in on our regularly curated interview segments called "Aliquots" released every week on our premium podcast The Aliquot. Aliquots come in two flavors: features and mashups.

- Hours of deep dive on topics like fasting, sauna, child development surfaced from our enormous collection of members-only Q&A episodes.

- Important conversational highlights from our interviews with extra commentary and value. Short but salient.

Sleep News

- High-intensity exercise in the evening may be associated with greater reductions of the hunger stimulating hormones

- The lullaby of the sun: the role of vitamin D in sleep disturbance. - PubMed - NCBI

- Microbiome Analysis Powers Insights to Improve Sleep

- Older people who have less slow-wave deep sleep were shown to have higher levels of tau tangles in the brain which is linked to Alzheimer's disease.

- Caffeine that was given to people 3 hours before normal bedtime caused a 40-minute shift in the body's internal clock.