The importance of early-day light for improved sleep | Matthew Walker

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The BDNF Protocol Guide

An essential checklist for cognitive longevity — filled with specific exercise, heat stress, and omega-3 protocols for boosting BDNF. Enter your email, and we'll deliver it straight to your inbox.

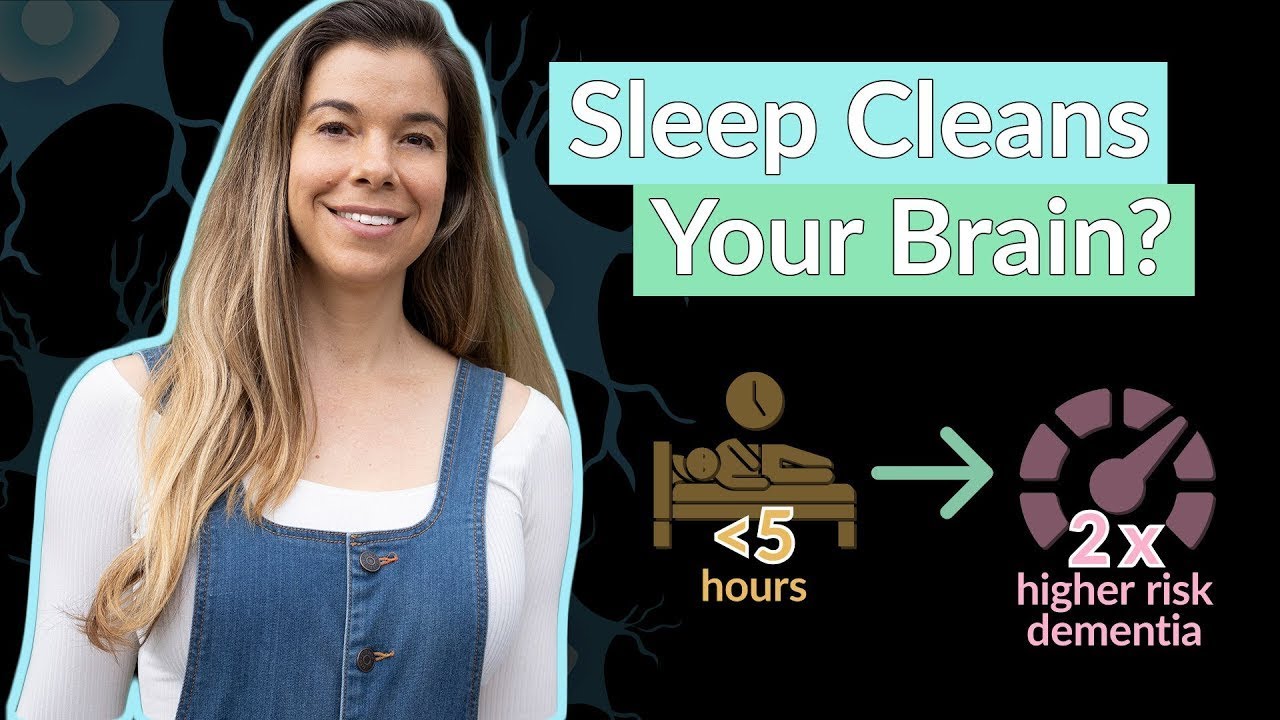

Our modern lifestyle – characterized by low light exposure during the day and high light exposure during the evening and nighttime hours – has dramatic effects on circadian rhythms and, ultimately, our ability to fall asleep and stay asleep. The key to restoring those rhythms to their natural, healthy patterns may be as simple as making small changes that alter the amount and timing of our exposure to light. In particular, exposure to 30 to 40 minutes of bright light, early in the day, and exposure to lower light during the afternoon and evening hours can reset our internal clocks and improve our sleep. In this clip, Dr. Matthew Walker explains how altering the timing and duration of daytime light exposure influences sleep.

Rhonda: Right. And to kind of just...Another point that you made talking about, you know, the hormonal response and the cortisol rising typically when it's supposed to be falling, that kind of prevents you from falling asleep, there is some interesting research that I've read where, and I know you and I have talked about how the importance of bright light exposure...Bright light exposure for six hours a day...I mean, no one does that nowadays. We're always inside. So it's rare unless you're, like, working out in a nature park or something.

Matt: The irony of these things...

Rhonda: Right, you know.

Matt: Yeah. It's for the camera. I promise.

Rhonda: Right. But, actually, it was shown to lower cortisol by 25%.

Matt: Yup.

Rhonda: So this is, like, you know, another kind of I don't know if that would even help someone with the anxiety or, you know...

Matt: No, I think it's...there's no studies testing it yet, but there are studies...So just sort of to go back to make this point, we normally have a circadian rhythm, this beautiful sort of 24-hour rhythm. And we human beings were diurnal, and we like to sleep at night, be awake during the day. We have this awesome upswing of our circadian rhythm sort of once we wake up sort of 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. It starts to peak during the day. It drops down a little bit in the mid-afternoon. And that's why you sort of get around meeting tables in the middle of the afternoon these sort of, you know, head nods. It's not people listening to good music. It's like, actually, it's a pre-programmed dip in your alertness. And then it rises back up, and then it drops down at night.

And one of the ways that you can get this sort of what you would want, which is a nice sinusoidal wave, you want a nice strong peak of the circadian rhythm during the day so that you're awake and you're active during the day and you're productive, and then you want an awesome sort of trough throughout the night so that you sleep soundly, deeply, and in a stable fashion.

And the way that you can sort of help your circadian rhythm have that wonderful peak and delightful trough is by getting lots of daylight during the day but lots of darkness during the night. And we are a dark-deprived society in this modern era. And it is a huge problem in the evening.

But I think people have underestimated that we are a light-deprived society during the day. So what happens is that your brain goes through life in this kind of almost stupor state where it's not getting enough daylight to really keep it ramped up throughout the day so you're sleepy throughout the day and you're tired, but then we've got too much light in the evening so you end up being awake at night, and then you're sleepy during the day, you're awake at night.

And so, you know, almost like, I'm gonna call it a seesaw. I think we call it teeter-totter here. You know, during the day, you want daylight to come in and force you all the way on to the on switch and you're active and awake. And then at night, you want the signal of darkness to come in to trigger the release of a hormone called melatonin to shift you all the way into the off position so you go into deep sleep and a sound sleep.

But now, with artificial light and staying out of bright light, so the teeter-totter has just pushed a little bit to one side, and then sort of with not enough darkness at night, it's only pushed a little bit down on the other side. So you kind of have this flip-flop switch that...it's like a dimmer switch that is basically just on dim for 24 hours rather than light and complete darkness, if that makes some sense.

Rhonda: Yes.

Matt: It's terrible analogy, but...

Rhonda: Do you have any idea, like, how much bright light exposure, like, you know...Let's say, you know, a lot of people work in, like, a little cubicle where they could don't even have windows. I mean, they're just like in the middle of this, like, little rooms with no actual sunlight coming in, you know, is something like if you wake up in the morning and you go outside for 30 minutes or an hour first thing in the morning, like...Most people are drinking their coffee. Well, maybe what you need is bright light exposure instead of your coffee, or drink your coffee outside.

Matt: Right, yeah. Take the coffee on...

Rhonda: Yeah. Do you know how much light you need? And if you don't have light outside, let's say you live in London, and you're in the winter, and there's no...It's just gray.

Matt: Even that, even on a cloudy day, the lux intensity of light far exceeds that that you would have from incandescent light or at sort of typical lights inside of a building.

Rhonda: Okay. So now my second question, the lux amount, so do you know?

Matt: Yeah. So I think, I mean, if you look at the studies, once you get over a sort of, you know, about 5,000 to 10,000 lux, you can have a pretty powerful effect. I don't believe there's...and I could be wrong. And Satchin Panda, our good friend, who is just A plus...In fact, yeah, if you're watching this, like, stop watching this now. Just go and watch the Satchin Panda podcast. He's much more powerful and eloquent than I am. But they have looked at the degree of exposure to outside light, not necessarily the intensity of light during that outside exposure time.

So I don't think we yet understand exactly what the dose response is in terms of lux intensity. What we do know is that getting 30 to 40 minutes of outside morning light is critical. But here's the trick. Here, in California a lot of people make this mistake, but even in London, it happens despite cloudy day, people put shades on in the morning. Don't do that. I know it looks good. But don't. Let that natural light penetrate your eye. There's a retinal mechanism that goes through to your thalamus that then goes through the hypothalamus that regulates your circadian clock. You need that light penetration. You're losing all of that good stuff if, or some of it, if you put shades on.

Wear some protection, that's fine. Just nix the shades in the morning. In the afternoon, reverse the trick. And this is actually a very good tip for jet lag. Jet lag is essentially an extreme form of what most of us have, which what we've been describing this diluted amount of light during the day and then too much light at night. Jet lag, you really should get out in the morning, 40 minutes of daylight, no shades. And in the afternoon, it's fine to go out. But when you go out, now is the time to put shades on, because you can start to encourage even then the release of melatonin, which is that hormone of darkness, which signals the timing of healthy sleep.

Rhonda: So about what time in the afternoon would you say shades are...?

Matt: So I would say, you know, probably...it depends on your bedtime, if you're a morning owl or an evening lark, and we can speak about chronotypes. So it really depends on when you're planning on going to bed. But let's say that you're planning on going to bed at about 10 p.m., I would say, if you're sort of going out after about to 4:30-ish, now is a good time to maybe start to help dilute down some of that light.

But then, you know, in the evenings, you know, we are so bathed and saturated in light. And yes, we can speak a lot about LED screens, and they are impactful, and there's been lots of work on that, some of which haven't replicated but many of which have. I think the bigger problem is just overhead lighting in general. We're just infused by, in every room that we go.

And my recommendation has now been, in the last hour before bed, just turn off half of the lights in your house, you know. We don't necessarily need all of them blazing in the last hour before bed. And when you do that, it's quite surprising how soporific and somnogenic it actually is, you know. And I want to do the experiment, although someone beat me to the experiment, and they did it...you know, it's one of those studies when I read it, I just thought, my first reaction, I'm not a big person. My first reaction was, oh, I'm so jealous.

Rhonda: Oh, yeah.

Matt: I was like, oh, I wish I've done...And then I just thought, this is a brilliant paper. I can't wait to teach it. They took a group of people. They looked at their habitual amount of sleep that they would typically get. And these people are getting sort of seven and a half to eight hours. And they would ask, you know, "When are you going to sleep?" And sort of most of them would go to bed like 11 and sleep through till 7.

And then they took them out of that typical, you know, modernity environment, and they took them out to the Rockies. And they had sleep tracking equipment on them. They took them there for several weeks. And there was no electricity whatsoever, not even a torch, not even a headlamp from a car, nothing. And then they look to see what changed.

The first thing was that these people went from sleeping, you know, an acclaimed seven and a half or seven hours of sleep that was their norm. It was actually just below seven, saying, "That was fine. That's all I needed." To then, actually, when they had no watch, they didn't know when to wake up, no alarm clocks, they ended up sleeping closer to nine hours a night, which is what we typically see when you saturate sort of people away from or dislocate them from modernity.

Rhonda: So would you say that's a good sleep duration?

Matt: Well, I think somewhere between seven to nine is what we recommend. But I think when you do this in a healthy, young people, and these were healthy, young people, they seemed to acclimate to a sleep amount that was somewhere between sort of eight to nine hours of sleep. So I think it's good evidence that, you know...You can look at how hunter-gatherer tribes were sleeping. And we've studied, you know, these people. And they actually sleep in a strange manner. We can get back to that. And people have tried to use them as the gold standard as to how we should be sleeping.

Rhonda: They're a lot more active and...I mean, they're so different, right?

Matt: I don't think it's a good control. I think we should say, "Let's take modern human beings and let's just take them out of all context of modernity. And let's see how they're sleeping. Let's just sort of put them on an ad-lib buffet of sleep. And they can just sleep as much as they want. They're not told when to wake up and sort of when to go to bed." And they seem to sleep what we now think of as a natural amount, which is somewhere between, if you look at the distribution, seven to nine hours.

Rhonda: And these are younger individuals? Sure.

Matt: Yup. And we can speak about, and I hope we speak about sleep and aging. But what was also interesting is when they slept, not just how much they slept. They started to go to bed earlier and earlier and earlier, and they started to wake up a little bit earlier and earlier. And the total duration of sleep expanded. But where that expanded amount of sleep was positioned on the 24-hour clock was dragged back because they weren't influenced by these cues of, you know, too much daylight at night. Temperature is another one that I'd love to speak about, too.

But what's fascinating is that when you look at hunter-gatherer tribes, all these experiments of sort of true nature, the natural point of middle point of sleep, the middle phase sort of time of that eight to nine hours sleep phase, came somewhere between midnight and 1:00 p.m. And I often ask people this question, you know, "Have you ever thought about what the term midnight actually means?" You know, it means the middle of the solar night, which is the time when most of us should be in the middle of our sleep phase.

But now, in the 21st century, we've gone through the, you know, the agrarian sort of, you know, pushed into the industrial era, and now into the digital era. Now midnight is the time when we maybe check Facebook for the last time or think about sending that last email. So not only has the duration of our sleep decreased through the influence of the modern times but also when we're sleeping has been dramatically shifted, too.

Rhonda: Right. I know I've made some changes a few years ago to my place, where now, I was telling you, I have Philips hue lights that turn on red light. And they come on actually quite early. They come on around 5 p.m. In fact, when we have visitors, they start to go crazy when sunset, and it's like red, and they're like getting sleepy, you know. It's like, "Why is it so dark in here? Can we turn the lights on?" And it's like, "No, because that's what you should...You're supposed to be getting the sleepy right now. You're supposed to be...It's 6:00, 6:30." Well, depending on what time of year it is, you know, "The sun is setting. You should be getting sleepy." It's phenomenal.

Matt: Yeah. It's one of the few triggers.

Rhonda: Yeah.

An individual’s innate tendency to sleep at a particular time during a 24-hour period. Chronotypes, which are based on circadian rhythms, are genetically determined. Disruption of a person’s chronotypic schedule can influence mood, productivity, and disease risk.

The body’s 24-hour cycles of biological, hormonal, and behavioral patterns. Circadian rhythms modulate a wide array of physiological processes, including the body’s production of hormones that regulate sleep, hunger, metabolism, and others, ultimately influencing body weight, performance, and susceptibility to disease. As much as 80 percent of gene expression in mammals is under circadian control, including genes in the brain, liver, and muscle.[1] Consequently, circadian rhythmicity may have profound implications for human healthspan.

- ^ Dkhissi-Benyahya, Ouria; Chang, Max; Mure, Ludovic S; Benegiamo, Giorgia; Panda, Satchidananda; Le, Hiep D., et al. (2018). Diurnal Transcriptome Atlas Of A Primate Across Major Neural And Peripheral Tissues Science 359, 6381.

A steroid hormone that participates in the body’s stress response. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone produced in humans by the adrenal gland. It is released in response to stress and low blood glucose. Chronic elevated cortisol is associated with accelerated aging. It may damage the hippocampus and impair hippocampus-dependent learning and memory in humans.

Animals characterized by higher activity during the day and sleeping more at night.

A region of the forebrain below the thalamus that coordinates both the autonomic nervous system and the activity of the pituitary, controlling body temperature, thirst, hunger, and other homeostatic systems, and involved in sleep and emotional activity.

A hormone that regulates the sleep-wake cycle in mammals. Melatonin is produced in the pineal gland of the brain and is involved in the expression of more than 500 genes. The greatest influence on melatonin secretion is light: Generally, melatonin levels are low during the day and high during the night. Interestingly, melatonin levels are elevated in blind people, potentially contributing to their decreased cancer risk.[1]

- ^ Feychting M; Osterlund B; Ahlbom A (1998). Reduced cancer incidence among the blind. Epidemiology 9, 5.

Sleep-promoting substances or activities. Somnogenic entities include exercise, meditation, and illness, among others.

A substance or activity that induces sleep. Soporifics include drugs, endogenous substances, meditation, and the lowering of lights in a room.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Hear new content from Rhonda on The Aliquot, our member's only podcast

Listen in on our regularly curated interview segments called "Aliquots" released every week on our premium podcast The Aliquot. Aliquots come in two flavors: features and mashups.

- Hours of deep dive on topics like fasting, sauna, child development surfaced from our enormous collection of members-only Q&A episodes.

- Important conversational highlights from our interviews with extra commentary and value. Short but salient.

Sleep News

- High-intensity exercise in the evening may be associated with greater reductions of the hunger stimulating hormones

- The lullaby of the sun: the role of vitamin D in sleep disturbance. - PubMed - NCBI

- Microbiome Analysis Powers Insights to Improve Sleep

- Older people who have less slow-wave deep sleep were shown to have higher levels of tau tangles in the brain which is linked to Alzheimer's disease.

- Caffeine that was given to people 3 hours before normal bedtime caused a 40-minute shift in the body's internal clock.