Sleep deprivation leads to a preference for carbohydrates and sugary snacks | Matthew Walker

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The Omega-3 Supplementation Guide

A blueprint for choosing the right fish oil supplement — filled with specific recommendations, guidelines for interpreting testing data, and dosage protocols.

Ghrelin, a hormone produced in the gut that signals hunger, acts on cells in the hypothalamus to stimulate appetite, increase food intake, and promote growth. It is often referred to as the "hunger hormone." Ghrelin’s effects are opposed by leptin, the “satiety hormone.” Sleep deprivation increases ghrelin levels and feelings of hunger while suppressing the satiety effects of leptin. Interestingly, these alterations are often accompanied by changes in food preferences, opting for high carbohydrate foods like pizza, pasta, and sweets. The downstream effects of these food choices are weight gain and metabolic dysfunction. In this clip, Dr. Matthew Walker describes how sleep deprivation drives a preferential desire for high carbohydrate foods.

Rhonda: Some of your work has shown that you're now also gonna have a preference to eat the very food that raises your blood sugar, right?

Matt: Yup, yup.

Rhonda: And it's something I've definitely experienced...

Matt: High glycemic food...

Rhonda: Yeah, yeah.

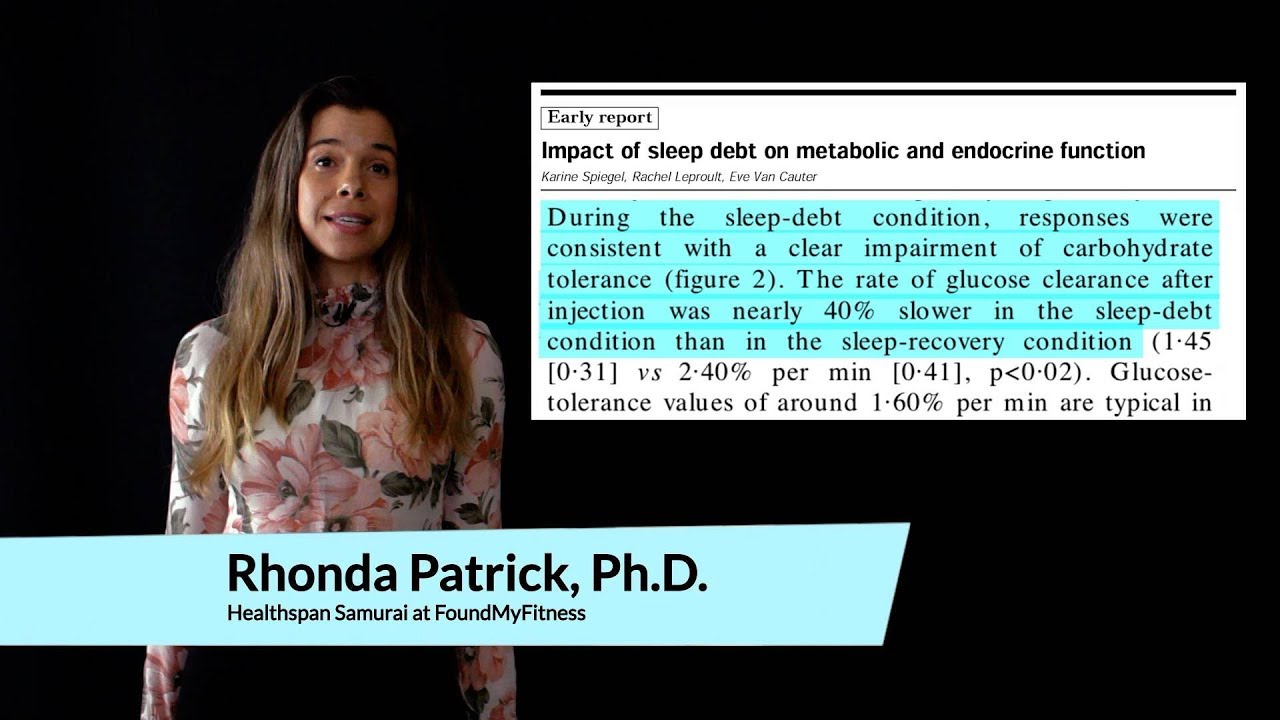

Matt: So this is a whole...So it all fits in, I think, to this energy balance. So, you know, firstly, what we know is that your regulation of blood sugar, of blood glucose is profoundly impaired by a lack of sleep. But what about your calorie intake? What about your obesogenic profile, setting aside your glycemic profile?

So what we've discovered is that when you're not getting enough sleep, two appetite-regulating hormones go in opposite directions. These two hormones are called leptin and ghrelin. And I often, you know, think of them as, you know, they sound like hobbits to me, at least, you know.

Rhonda: That's hilarious.

Matt: Leptin and ghrelin that, you know, J. R. Tolkien would have written about them. But they're not. They're real hormones. Leptin is a hormone that signals satiety. What I mean by that is, when you have high amounts of leptin, it tells your brain you're full. You're satisfied with your food. You don't want to eat anymore. Ghrelin is the other hunger hormone. When ghrelin is increased, you feel unsatisfied by your food. You feel hungry. And you want to eat more.

So after you eat a meal, normally, what happens is that levels of leptin increase and levels of ghrelin, the hunger hormone, you can think about ghrelin as like a grumbling tummy, ghrelin goes down. And this means that you stop eating, you don't want to eat anymore, and you're full for a duration of time period. When you are sleep-deprived, levels of leptin, which normally signal to your brain you're full and you're satisfied with food, that hormone is impaired by a lack of sleep. So you lose the fullness satiety signal in your brain.

If that wasn't bad enough, the hunger hormone, ghrelin, actually increases. So it's a double whammy effect here. What does that lead to? It leads to a strong obesogenic profile of energy consumption, of food consumption. So what we, and Eve Van Carter, in fact, has done all of these pioneering studies, and we've done some of them now, too, typically, you tend to overeat during main meals. So you will typically eat somewhere between about 200 to 300 extra calories. If we give you a meal, and we measure all of the food on your plate, and we ask how much did you eat at that one sitting, you tend to overeat by about 200 or 300 calories per main meal sitting.

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: Now you could say...Well, actually...

Rhonda: That's after a full night of sleep?

Matt: Well, that's when you've been limited to maybe four hours of sleep for a week. Now someone, and the reviewers of these papers, you know, in the early days, said, "Well, that's because when you're awake longer, being awake is more metabolically demanding, and you're probably moving around more." Not true. It turns out sleep, firstly, is a remarkably metabolically active state. You're very active metabolically when you're asleep. In fact, the difference between being asleep versus being awake is only about, for a whole night of sleep, the difference of about 140 calories.

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: Just like a small cookie, essentially. So, yes, when you're awake longer, you do burn more calories. But the amount of calories that you increase in your intake far exceeds anything that you expend by way of being awake a little bit longer. If that wasn't bad enough, though, it's not the main meal where the trouble lies with sleep. That's some of the problem.

The other studies that are even more sort of devilish are where you give these sleep-deprived subjects the same meal but then you give them a snack bar. And it's an ad-lib food buffet, essentially. And you can eat as much as you want. And they allow you to eat in a room by yourself, so there's no social pressure, so you don't restrict your eating or...it's true eating.

And of course, we measure everything that you eat. And it's snacking that is the dead giveaway here. You end up eating 300 to 400 additional calories by way of snacks. This is after they've eaten a 2,000-calorie meal in one sitting. They will then go away, and they will eat an additional 400 calories at the snack bar.

Rhonda: Wow.

Matt: So, as a consequence, what you're doing is you're increasing the total caloric intake, which sets you on a path towards being overweight and obese. Then the discovery came that it's not just what you eat...sorry, it's not just how much you eat but it's what you eat. And what Eve Van Carter discovered in her early studies was that if you give one of these sort of food buffets...and you can eat anything. It goes from, you know, sugary treats to salty treats like pretzels or potato chips to heavy-hitting starchy carbohydrates, breads, pasta, pizza all the way to salad, what you find is that you eat more of all of the food groups. But you eat mostly in terms of an increase the starchy, heavy-hitting carbohydrates as well as the sugary foods.

And if we know anything from the recent movement in food, particularly from people like Gary Taubes, who has written wonderfully about this type of stuff, that's the food that sets you on a path, again, down an obesogenic and also a poor glycemic control profile. If you look at all of the cardiometabolic markers of health when you're eating excessive carbohydrate-heavy rich or and particularly simplified sugars, they're bad for your health profile in general. It's exactly the foods that you eat when you are underslept.

Rhonda: Is there a feedback loop on those foods affecting your sleep?

Matt: There is.

Rhonda: There is.

Matt: So I would say this is probably, apart from maybe the gut microbiome of which there is now some evidence, and we're starting to look at this, too, at the sleep center, it's probably the least well understood. But the bottom line is that if you're eating a diet that's high in carbohydrate, especially high in processed simple sugars and low in fiber, you tend to have worse sleep, you take longer time to fall asleep, the amount of deep sleep that you get is less, and you have more fragmented awakenings throughout the night.

A hormone produced in the gut that signals hunger. Ghrelin acts on cells in the hypothalamus to stimulate appetite, increase food intake, and promote growth. Ghrelin’s effects are opposed by leptin, the “satiety hormone.” Sleep deprivation increases ghrelin levels and feelings of hunger, which can lead to weight gain and metabolic dysfunction.

A region of the forebrain below the thalamus that coordinates both the autonomic nervous system and the activity of the pituitary, controlling body temperature, thirst, hunger, and other homeostatic systems, and involved in sleep and emotional activity.

A hormone produced primarily by adipocytes (fat cells) that signals a feeling of satiety, or fullness, after a meal. Leptin acts on cells in the hypothalamus to reduce appetite and subsequent food intake. Leptin’s effects are opposed by ghrelin, the “hunger hormone.” Both acute and chronic sleep deprivation decrease leptin levels.

The collection of genomes of the microorganisms in a given niche. The human microbiome plays key roles in development, immunity, and nutrition. Microbiome dysfunction is associated with the pathology of several conditions, including obesity, depression, and autoimmune disorders such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, and fibromyalgia.

A type of polysaccharide – a large carbohydrate consisting of many glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. Starch is produced by plants and is present in many staple foods, such as potatoes, wheat, maize (corn), rice, and cassava. It is the most common carbohydrate in human diets. Pure starch is a white, tasteless, and odorless powder.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Get email updates with the latest curated healthspan research

Support our work

Every other week premium members receive a special edition newsletter that summarizes all of the latest healthspan research.

Sleep News

- High-intensity exercise in the evening may be associated with greater reductions of the hunger stimulating hormones

- The lullaby of the sun: the role of vitamin D in sleep disturbance. - PubMed - NCBI

- Microbiome Analysis Powers Insights to Improve Sleep

- Older people who have less slow-wave deep sleep were shown to have higher levels of tau tangles in the brain which is linked to Alzheimer's disease.

- Caffeine that was given to people 3 hours before normal bedtime caused a 40-minute shift in the body's internal clock.