Chronotypes: Your natural propensity to be an early riser or night owl | Matthew Walker

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The BDNF Protocol Guide

An essential checklist for cognitive longevity — filled with specific exercise, heat stress, and omega-3 protocols for boosting BDNF. Enter your email, and we'll deliver it straight to your inbox.

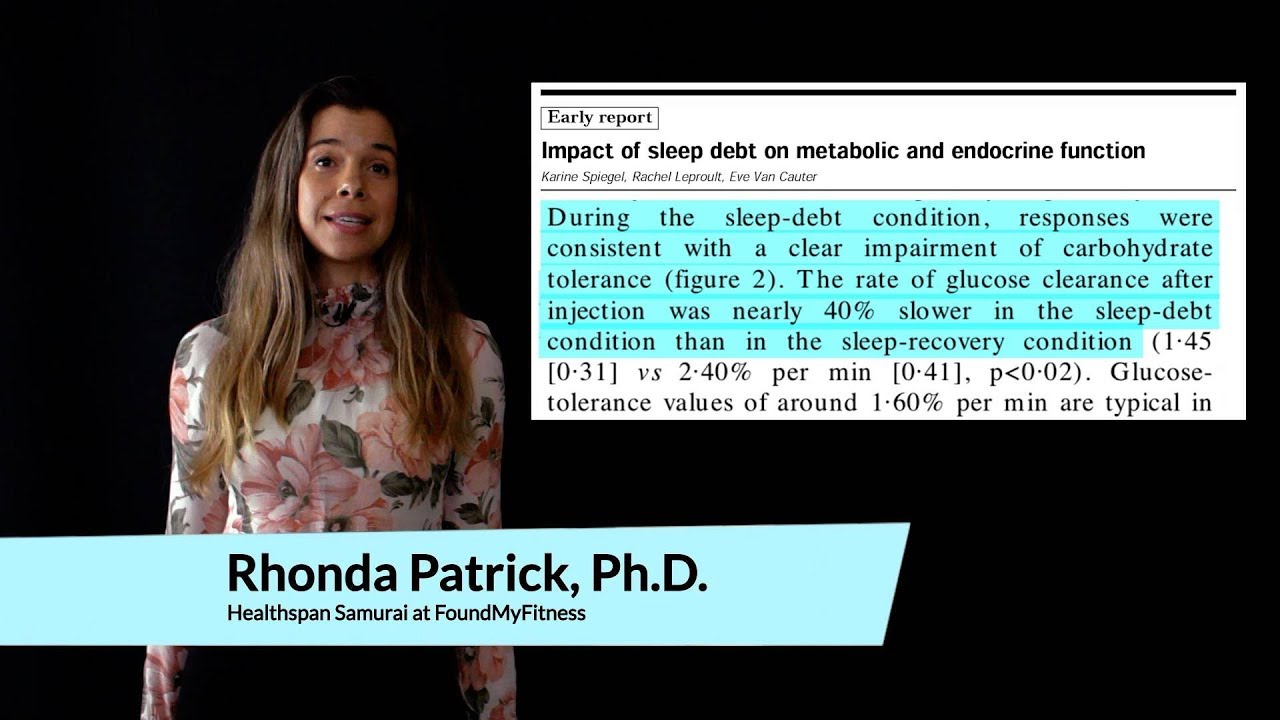

A person's chronotype, their innate tendency to sleep at a particular time during a 24-hour period, is based strongly on genetically determined circadian rhythms. Disruption of a person’s chronotypic schedule can influence mood, productivity, and disease risk because it may interfere with the duration of their REM sleep, which is essential for emotional well-being. In this clip, Dr. Matthew Walker describes the different chronotypes and the risks associated with adopting a sleep pattern that is contrary to our natural type.

Matt: So I mentioned that just coming back to the quality of sleep, when you position the quantity of sleep on the clock face, on the 24-hour clock face, at an inappropriate time according to your natural innate preference, and I say that specifically rather than a particular time, you will not get the same quality of your sleep. So an extreme version of this is a night shift worker, where they may get eight hours of sleep in bed but they are sleeping during the day, not during the night. So it's a complete reversal. The quality of their sleep is not good. They don't get the same amount of deep sleep nor do they get the same amount of REM sleep.

But let's kind of walk that back a little bit to your scenario, which is much more subtle. Let's say that my chronotype, and your chronotype simply determines whether you're a morning person, an evening person, or somewhere in the middle, about 30% of the population is an extreme morning type or a morning type, about sort of 40% percent is sort of neither strongly morning or evening, and about the remaining 30% is an evening type, we call them owls and larks.

So if you're a morning type, you like to go to bed, let's say, like, 9 p.m. And wake up at 5 or 6. If you're an evening type, you may want to go to bed at 1 a.m. And wake up at 9 a.m. The next morning. So when I'm saying the optimal position of sleep, I'm saying with the optimal for your chronotype, this is your chronotype...And by the way, it's genetic. You don't get to decide whether you're a morning type or an evening type. It's hardwired into your genes. We know the genes. It's not your fault. If you're an evening type and you're listening to this, and society, which is strongly architected against your chronotype, we reward and we favor the morning types, it is not your fault. It's not a choice. And there's not too much you can do about it. You can push and pull the system by about 30 minutes, 45 minutes, but not much more.

So coming back to it, when we position that sleep on that eight-hour period, whatever is optimal for you, you will get a nice distribution. You'll get all of the deep sleep that you want and all of the REM sleep that you want. And earlier in the conversation, I said that we go through these 90-minute cycles, we, human beings, it's different for different animals, you always go into deep non-REM sleep first and then you always have REM sleep second. And that repeats every 90 minutes throughout the night.

What changes, however, is the ratio of non-REM to REM within those 90-minute cycles as you move across the night such that in the first half of the night, the majority of those 90-minute cycles are comprised of lots of deep non-REM sleep and very little REM sleep. In the second half of the night, that balance shifts, and now you get much more REM sleep in the late morning hours and very little deep sleep.

The reason I'm saying this is because let's take someone who goes to bed at a substandard amount of time. Let's say that they go to bed at midnight, and they're going to wake up at 8. But instead they have to wake up, because they've got an early morning meeting, so they go to bed at midnight and they wake up at 6. And my question is how much sleep have they lost? And your response is, well, they've lost two hours out of the eight hours, which means they've lost 25% of their sleep. And your answer would be right in a way, but it would be wrong as well, which is that they've lost 25% of their total sleep but they may have lost almost 80% of their REM sleep because that's the REM rich phase of the night.

And it also works the other way around, too, that if you go to bed too late, you will...So what happens is, because of the circadian rhythm, the brain has a different appetite for different stages of sleep on the 24-hour clock face. In the late evening and the early morning hours, the brain has a dietary preference for deep sleep. And it doesn't very much have an appetite taste for REM sleep. Through to the second half of the night, that's when it gets its appetite for REM sleep.

So if you start sleeping at 4:00 in the morning and you wake up it in the middle of the day, your brain has lost its appetite for deep sleep. And so it won't get much. Now you will probably get much more REM sleep as a consequence. So you've got to be really careful. That why...

Rhonda: So it's almost like your chronotype may even dictate in a way how much deep sleep you may get.

Matt: The chronotype will...If you sleep naturally and you get the amount of sleep that you want, your chronotype will probably mean that...your circadian rhythm is actually shifted as your chronotype, too. So you will still get, as an owl, if you get your eight hours when you want it, you will probably get a similar sleep architecture as a lark, who has gone to bed five or six hours earlier, because your circadian rhythms are five to six hours different.

But you're right in the sense that owls typically try to go to bed early. But because they are designed not to fall asleep at that time, they're just gonna lie in bed. Many owls think that they have insomnia. They don't. They're just not going to bed at the right time. Because they get into bed, and it's like a teenager, whose rhythm is also shifted late, you tell them to go to bed because you've got to wake up for early school start times, but there's nothing they can do because their circadian rhythm has shifted forward in time. And it's the same for owls.

So what will happen is that they will probably stay awake for a while, then they'll get into deep sleep. But then they have to wake up at an earlier time, and they will lose a lot of REM sleep. REM sleep, for emotional well-being, what the owls typically experience: depression, low mood, anxiety. So I think we're really starting to put the pieces together on that component.

Rhonda: And so for someone like me, I'm somewhere in the middle, like, when I don't...pre-baby. Now I'm I guess you would call a lark because I'm going to bed at, like, 9. My optimal time, if I can go to bed when my son does, and it's like, you know, if I go to bed, like, at 8, then I get the longer duration. That way, if I'm a little more fragmented, then I, like, at least can make up for it somewhat. But I'm up at 6 a.m. Now if it were up to me, I'd like to sleep...I usually would wake up, like, 8 a.m.

Matt: Yes, 8 a.m.

Rhonda: Like, that's my natural time.

Matt: And the reason that you can probably go to sleep sort of, you know, 9 p.m. Or even 8 p.m. Now is because you're chronically sleep-deprived. And as a consequence, you've built up such as sleep debt that, you know, there is a lingering what we call sleep pressure in your system. But, yeah, I think fighting your chronotype, we found, it comes with deleterious health consequences. Increased risk for poor cardio-metabolic outcomes. Things like, you know, C-reactive protein is higher. If you look at, you know, A1C in terms of sort of a Rorschach review of blood glucose, your blood sugar, not good. If you look at your propensity for being obese or being overweight, also not great if you're an owl and you're not sleeping according to your schedule.

Rhonda: Telomeres are shorter.

An individual’s innate tendency to sleep at a particular time during a 24-hour period. Chronotypes, which are based on circadian rhythms, are genetically determined. Disruption of a person’s chronotypic schedule can influence mood, productivity, and disease risk.

The body’s 24-hour cycles of biological, hormonal, and behavioral patterns. Circadian rhythms modulate a wide array of physiological processes, including the body’s production of hormones that regulate sleep, hunger, metabolism, and others, ultimately influencing body weight, performance, and susceptibility to disease. As much as 80 percent of gene expression in mammals is under circadian control, including genes in the brain, liver, and muscle.[1] Consequently, circadian rhythmicity may have profound implications for human healthspan.

- ^ Dkhissi-Benyahya, Ouria; Chang, Max; Mure, Ludovic S; Benegiamo, Giorgia; Panda, Satchidananda; Le, Hiep D., et al. (2018). Diurnal Transcriptome Atlas Of A Primate Across Major Neural And Peripheral Tissues Science 359, 6381.

A ring-shaped protein found in blood plasma. CRP levels rise in response to inflammation and infection or following a heart attack, surgery, or trauma. CRP is one of several proteins often referred to as acute phase reactants. Binding to phosphocholine expressed on the surface of dead or dying cells and some bacteria, CRP activates the complement system and promotes phagocytosis by macrophages, resulting in the clearance of apoptotic cells and bacteria. The high-sensitivity CRP test (hsCRP) measures very precise levels in the blood to identify low levels of inflammation associated with the risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

A mood disorder characterized by profound sadness, fatigue, altered sleep and appetite, as well as feelings of guilt or low self-worth. Depression is often accompanied by perturbations in metabolic, hormonal, and immune function. A critical element in the pathophysiology of depression is inflammation. As a result, elevated biomarkers of inflammation, including the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, are commonly observed in depressed people. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behavioral therapy typically form the first line of treatment for people who have depression, several non-pharmacological adjunct therapies have demonstrated effectiveness in modulating depressive symptoms, including exercise, dietary modification (especially interventions that capitalize on circadian rhythms), meditation, sauna use, and light therapy, among others.

A blood test that measures the amount of glycated hemoglobin in a person’s red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test is often used to assess long-term blood glucose control in people with diabetes. Glycation is a chemical process in which a sugar molecule bonds to a lipid or protein molecule, such as hemoglobin. As the average amount of plasma glucose increases, the fraction of glycated hemoglobin increases in a predictable way. In diabetes mellitus, higher amounts of glycated hemoglobin, indicating poorer control of blood glucose levels, have been associated with cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy. Also known as HbA1c.

A phase of sleep characterized by slow brain waves, heart rate, and respiration. NREM sleep occurs in four distinct stages of increasing depth leading to REM sleep. It comprises approximately 75 to 80 percent of a person’s total sleep time.

A distinct phase of sleep characterized by eye movements similar to those of wakefulness. REM sleep occurs 70 to 90 minutes after a person first falls asleep. It comprises approximately 20 to 25 percent of a person’s total sleep time and may occur several times throughout a night’s sleep. REM is thought to be involved in the process of storing memories, learning, and balancing mood. Dreams occur during REM sleep.

A person who works on a schedule outside the traditional 9 AM – 5 PM day. Work can involve evening or night shifts, early morning shifts, and rotating shifts. Many industries rely heavily on shift work, and millions of people work in jobs that require shift schedules.

Distinctive structures comprised of short, repetitive sequences of DNA located on the ends of chromosomes. Telomeres form a protective “cap” – a sort of disposable buffer that gradually shortens with age – that prevents chromosomes from losing genes or sticking to other chromosomes during cell division. When the telomeres on a cell’s chromosomes get too short, the chromosome reaches a “critical length,” and the cell stops dividing (senescence) or dies (apoptosis). Telomeres are replenished by the enzyme telomerase, a reverse transcriptase.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Attend Monthly Q&As with Rhonda

Support our work

The FoundMyFitness Q&A happens monthly for premium members. Attend live or listen in our exclusive member-only podcast The Aliquot.

Sleep News

- High-intensity exercise in the evening may be associated with greater reductions of the hunger stimulating hormones

- The lullaby of the sun: the role of vitamin D in sleep disturbance. - PubMed - NCBI

- Microbiome Analysis Powers Insights to Improve Sleep

- Older people who have less slow-wave deep sleep were shown to have higher levels of tau tangles in the brain which is linked to Alzheimer's disease.

- Caffeine that was given to people 3 hours before normal bedtime caused a 40-minute shift in the body's internal clock.