Importance of myrosinase in supplements for the conversion of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane | Jed Fahey

Enter your email to get our 15-page guide to sprouting broccoli and learn about the science of chemoprotective compount sulforaphane.

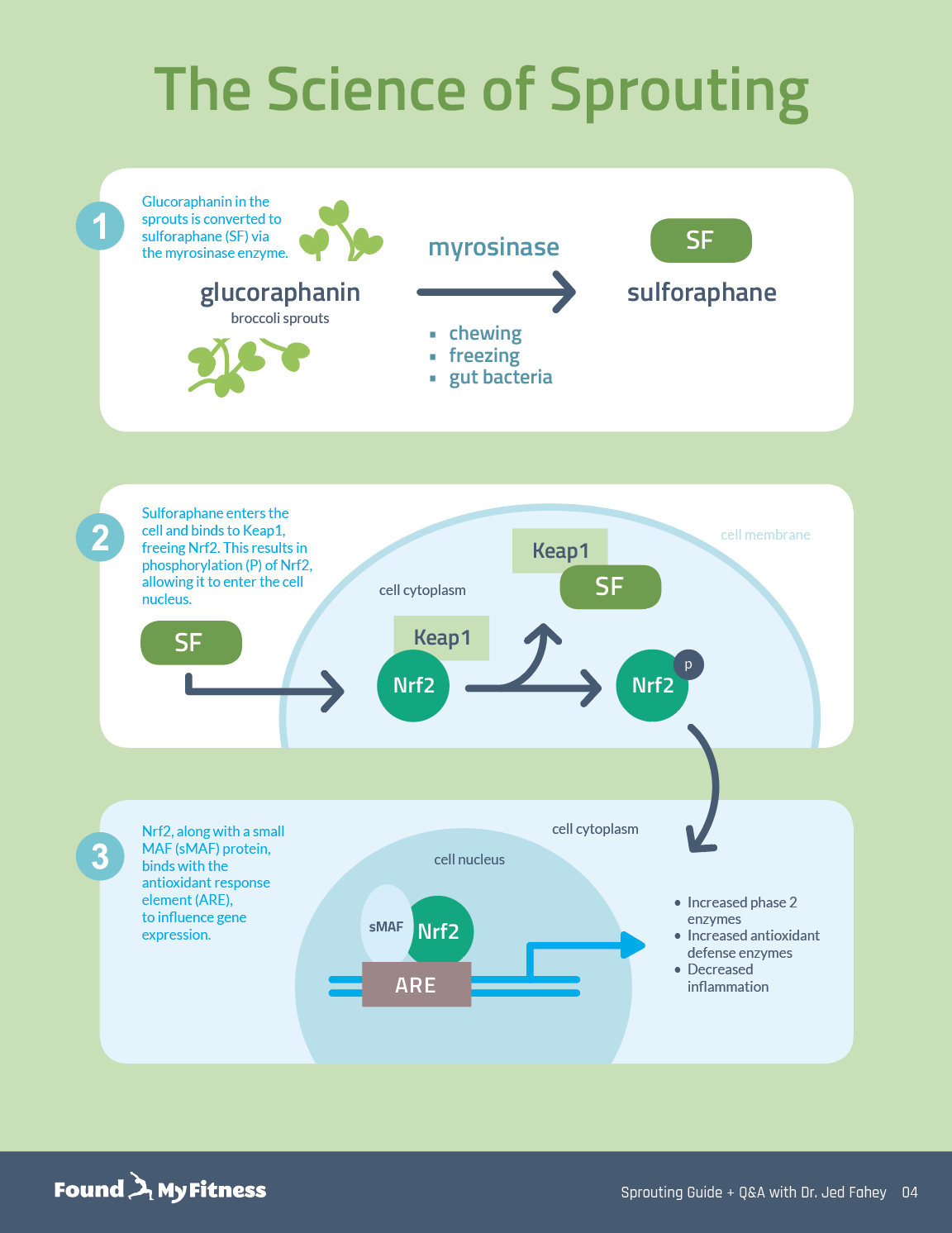

Broccoli sprouts are concentrated sources of sulforaphane, a type of isothiocyanate. Damaging broccoli sprouts – when chewing, chopping, or freezing – triggers an enzymatic reaction in the tiny plants that produces sulforaphane.

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

A few dietary supplement manufacturers have partnered with the Cullman Chemoprotection Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine to produce quality supplements that contain both glucoraphanin and active myrosinase. These supplements have demonstrated efficacy in a number of recent clinical trials. The inclusion of active myrosinase is critical in clinical trials because although myrosinase-producing gut bacteria can convert unhydrolyzed glucosinolates to their cognate isothiocyanates, the conversion rate is highly variable and subject to interindividual differences in gut bacteria populations. In this clip, Dr. Jed Fahey discusses the importance of having active myrosinase in dietary supplements for optimizing the conversion of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane.

Jed: So a couple of years ago, I went to a small number of supplement companies and said, "Help," and challenged them to take the supplements that they were making that we had tested and verified contained what they said they had and to offer to supply them for clinical trials that we were approached about partnering on. And not only to supply the material free of charge, but to supply all the documentation and paperwork that would go along with an application to an institutional review board or to the FDA, in fact, for an investigational new drug application for permission to work on that disease with that compound. And a few companies did come forward. One of them was called Nutramax and they have a product called Avmacol, which they sort of took a page from our playbook and they made something with glucoraphanin and myrosinase.

And so that's actually been used in a number, quite a large number of clinical trials now. And so I don't think... We've tested it in people, of course. I don't think there's anything ready to be published yet, but those publications will be coming along very shortly.

Rhonda: And that actually does contain the glucoraphanin and myrosinase and you've validated that?

Jed: Yes, we would certainly not recommend something to anybody without checking it. And we've checked every batch that they've put on the market because we don't want to be in a position... I don't want to have egg on my face, and have recommended to a friend that this is a product worth using and then have it turn out to be a dud.

Rhonda: So you mentioned the sulforaphane one, which is the Prostaphane, the Avmacol, which has the glucoraphanin plus the myrosinase, and then there's the one that just has glucoraphanin. I think you mentioned it was by Thorne?

Jed: They're one of a number of companies that have a decent...I shouldn't say that have a decent one. They're probably if you put this on a webinar, there are probably going to be 10 companies that say, "We have a decent one, too." I'm sure there are others, but we've tested...

Rhonda: You've tested, and that's important.

Jed: Yes, we've tested a product by Thorne, which is a medium or a large-size supplement maker, and their product is called Crucera-SGS.

Rhonda: But that only has glucoraphanin in it?

Jed: Right.

Rhonda: And this actually brings me back to...I kinda want to get back to this and that is the microbiome. And so if you're taking a supplement that only has glucoraphanin and does not have the myrosinase enzyme there, then you're relying on what you possibly potentially have in a species of bacteria in the gut, which maybe you can illuminate what that species of bacteria is, or if there's ways we can increase it, probiotics. Obviously, wiping out the gut bacteria. So people with chronic antibiotic use may not be able to convert glucoraphanin very well, the sulforaphane, I would presume.

Jed: Right. You must have read one of our papers. So in fact, we did show that, this was a number of years ago now, we showed that if volunteers took a Fleet enema, self-administered enema, which reduces the number of bacteria, certainly in their large intestine, by, I don't know, five or six orders of magnitude, and took a preoperative antibiotic course, in other words, something that one would take prior to having intestinal surgery, they essentially wiped out most of the bacteria in their intestines. And those people went from whatever their level of conversion of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane and its metabolites was, which was, as you heard earlier, was 10% to 70% to nothing. So they lost their ability to convert glucoraphanin to sulforaphane.

And then over the course of a couple of weeks, I think, as I recall, we followed them, one or two subsequent challenges with glucoraphanin two weeks and four weeks later, I think. They gradually regained their ability to do that reaction. Clearly residual bacteria or new colonizers in their guts had myrosinase activity. So we've looked at hundreds and hundreds of people's ability to do this conversion and nobody can't do it. So everybody that's living and breathing appears to have myrosinase-producing bacteria in their gut. But as we said earlier, obviously, it's at very different levels.

Just as clearly, although we don't do bacterial sequencing here, and this is a new and very exciting field of the microbiome, but it's very clear that there are certain strains or certain species of bacteria that do have myrosinase activity. Others have shown that there are, I believe one of them is enterococcus, there are lactobacilli that have myrosinase activity. There are Bifidobacterium, I believe, that have it. And again, this is not my field of expertise, so I may have misspoken. But the bottom line is that there are a number of species of bacteria that do this, but certainly not all bacteria in your gut.

This whole, incredibly fascinating field of the microbiome has certainly shown that each of us has different populations and different ratios of different types of bacteria in our guts. And certainly, to the degree that this is true, that's going to affect the amount of myrosinase activity in our guts. I can tell you that we have done, we haven't published this, but we've done studies with mice in which we've challenged them with glucoraphanin on a regular basis over time. And the goal was to try to push them by natural selection, to try to push them to have more bacteria with more myrosinase activity. The fact that we haven't published it means we didn't move the needle well enough or reproducibly enough to have a good story to tell, but certainly that's what we believe might happen.

Having said that, we look at real people and we query them as to their habits. There is no evidence to date that people who say they eat a pound of broccoli a day, that's a little bit of an exaggeration, but people who eat a lot of broccoli don't necessarily convert glucoraphanin better than people who don't eat much at all. So that speaks to some other selective pressure on the gut on myrosinase-containing bacteria.

Rhonda: Yeah. I would think that even just eating a healthy meal in general when you're eating a diet high in vegetables and fermentable fibers and things that are growing Bifidobacteria and lactobacillus and all these species of bacteria that are commensal bacteria, that even that itself would potentially then increase your chances of being able to have more myrosinase because you're having more of this commensal microbiome, but I guess we don't know.

Jed: You know, we don't know. I think both of our hunches are correct. But the proof is in the pudding. This whole issue of probiotics...

Rhonda: Yes. That was going to be my next question. That would be interesting to view.

Jed: Well, it's fascinating. You know, in Europe, there is a lot, I think the regulatory climate in Europe for probiotics is a bit more receptive than in the U.S. You probably know more about it than I do. But I know that the use of probiotics seems to be increasing in the U.S., and studies by those who are expert in the field of probiotics are mixed.

Rhonda: Well, it's the same case as the glucoraphanin sulforaphane supplements. A lot of the probiotics in the market, there is a lot of dead bacteria in them...

Jed: A lot of garbage, yeah.

Rhonda: ...a lot of garbage. I mean, this is ubiquitous in all supplements. You know, I think there was even a study showing something like 70% of, like, a lot of these supplements on the market are not actually what they say they are, they don't have the concentrations they say. But, yeah, I think that there is a lot of mixed data and that comes down to not having quality probiotics and also the numbers. That's another problem, too low numbers of....

Jed: Right, 10 billion per...

Rhonda: Yeah, that's nothing. You know, it's like a drop in the pool. It's not going to even move the needle. But there is a probiotic out there that I've seen at least two dozen publications including clinical trials in humans and then there's more mechanistic studies in animals using VSL #3. It's called, they're sachets and they have 450 billion probiotics per sachet and they have a mixture of lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and some other ones but showing efficacy in treating IBS, Crohn's. You know, so I think you can find quality probiotics, but it's just, again, it's the same thing that you've seen in your field, is finding the right one.

Jed: Absolutely. I think the issue of the numbers of cells, I mean, to a non-scientist consumer, "billions" sounds like a huge number. Well, yeah, it is, but it's still...you know, you can fit a billion bacteria on a pin, probably, well, maybe a teaspoon. Anyway, the issue there, though, is a lot of the issue is survival. So if you boast about having billions of bacterial cells of a certain type in yogurt, for example, and you're not on proton pump inhibitors, so you have an acid stomach and you send that yogurt through your stomach, how many of those bacteria actually make it through the acid environment of the stomach? So, I mean, people have studied that certainly, but there are studies, as you say, with a small number of specific strains showing effects. I think some of the more striking effects have to do with childhood diarrhea and there are even studies showing effects on asthma.

Rhonda: Effects on the brain. It's incredible.

Jed: Yeah. So I'm absolutely a believer that what's goes on in the gut matters to the rest of the body. There is no question about it. I think, as you say, a lot of the studies suffer from the fact that what's being given probably couldn't have been expected to be efficacious anyway because it just died or didn't get there. But speaking of probiotics, wouldn't it be cool if someone came up with a myrosinase containing strain and put it in a probiotic formulation so that you could take that along with your cruciferous vegetables?

Rhonda: So cool.

Jed: I believe that there are companies that are working on that now because certainly, it's well enough known what strains of bacteria have myrosinase activity. There may be issues of getting that activity maintained when you grow up vats full of bacteria to freeze-dry them, to put them in a formulation. But I hope it's only a matter of time before we see formulations that contain myrosinase and that are safe. I mean, obviously, safety of these probiotic formulations is something that is a concern to the regulators and it should be. So we'll see. I don't think we're quite there, but I hope we are getting there.

A genus of bacteria known to inhabit the human gut. Bifidobacteria are anaerobic commensal bacteria. They are among the first bacteria to colonize the infant gut and may play critical roles in gut-mediated immune function.

Bacteria that are beneficial or at least not harmful to the host, in contrast to pathogenic bacteria where the host derives no benefit and is actively harmed from the relationship. Roughly 100 trillion commensal bacteria live in the human gut. The term commensal comes from Latin and literally means “eating at the same table.”

An inflammatory bowel disease that causes inflammation of the lining of the digestive tract, which can lead to abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss and malnutrition.

Any of a group of complex proteins or conjugated proteins that are produced by living cells and act as catalyst in specific biochemical reactions.

A glucosinolate (see definition) found in certain cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and mustard. Glucoraphanin is hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase to produce sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate compound that has many beneficial health effects in humans.

A group of symptoms—including abdominal pain and changes in the pattern of bowel movements without any evidence of underlying damage. It has been classified into four main types depending on if diarrhea is common, constipation is common, both are common, or neither occurs very often. The causes of IBS are not clear.

Byproduct of a reaction between two compounds (glucosinolates and myrosinase) that are found in cruciferous vegetables. Isothiocyanates inhibit phase I biotransformation enzymes, a class of enzymes that transform procarcinogens into their active carcinogenic state. Isothiocyanates activate phase II detoxification enzymes, a class of enzymes that play a protective role against DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species and carcinogens. Examples of phase II enzymes include UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, sulfotransferases, N-acetyltransferases, glutathione S-transferases, and methyltransferases.

The collection of genomes of the microorganisms in a given niche. The human microbiome plays key roles in development, immunity, and nutrition. Microbiome dysfunction is associated with the pathology of several conditions, including obesity, depression, and autoimmune disorders such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, and fibromyalgia.

A family of enzymes whose sole known substrates are glucosinolates. Myrosinase is located in specialized cells within the leaves, stems, and flowers of cruciferous plants. When the plant is damaged by insects or eaten by humans, the myrosinase is released and subsequently hydrolyzes nearby glucosinolate compounds to form isothiocyanates (see definition), which demonstrate many beneficial health effects in humans. Microbes in the human gut also produce myrosinase and can convert non-hydrolyzed glucosinolates to isothiocyanates.

Environmental factors which may reduce reproductive success in a population and thus contribute to evolutionary change or extinction through the process of natural selection.

An isothiocyanate compound derived from cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and mustard. Sulforaphane is produced when the plant is damaged when attacked by insects or eaten by humans. It activates cytoprotective mechanisms within cells in a hormetic-type response. Sulforaphane has demonstrated beneficial effects against several chronic health conditions, including autism, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and others.

Hear new content from Rhonda on The Aliquot, our member's only podcast

Listen in on our regularly curated interview segments called "Aliquots" released every week on our premium podcast The Aliquot. Aliquots come in two flavors: features and mashups.

- Hours of deep dive on topics like fasting, sauna, child development surfaced from our enormous collection of members-only Q&A episodes.

- Important conversational highlights from our interviews with extra commentary and value. Short but salient.

Sulforaphane News

- Sulforaphane extends lifespan and healthspan in worms via insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling.

- Paul Saladino, MD explains how we may have overstated the health benefits of plants and especially sulforaphane

- NRF2 much of a good thing (December 2017)

- A pilot trial finds sulforaphane treatment increased glutathione levels in the blood & hippocampus region of the brain in healthy people.

- A new study found sulforaphane (found in broccoli sprouts) improved behavior & social responsiveness in children with autism.