Is Moringa as effective as sulforaphane? | Jed Fahey

Enter your email to get our 15-page guide to sprouting broccoli and learn about the science of chemoprotective compount sulforaphane.

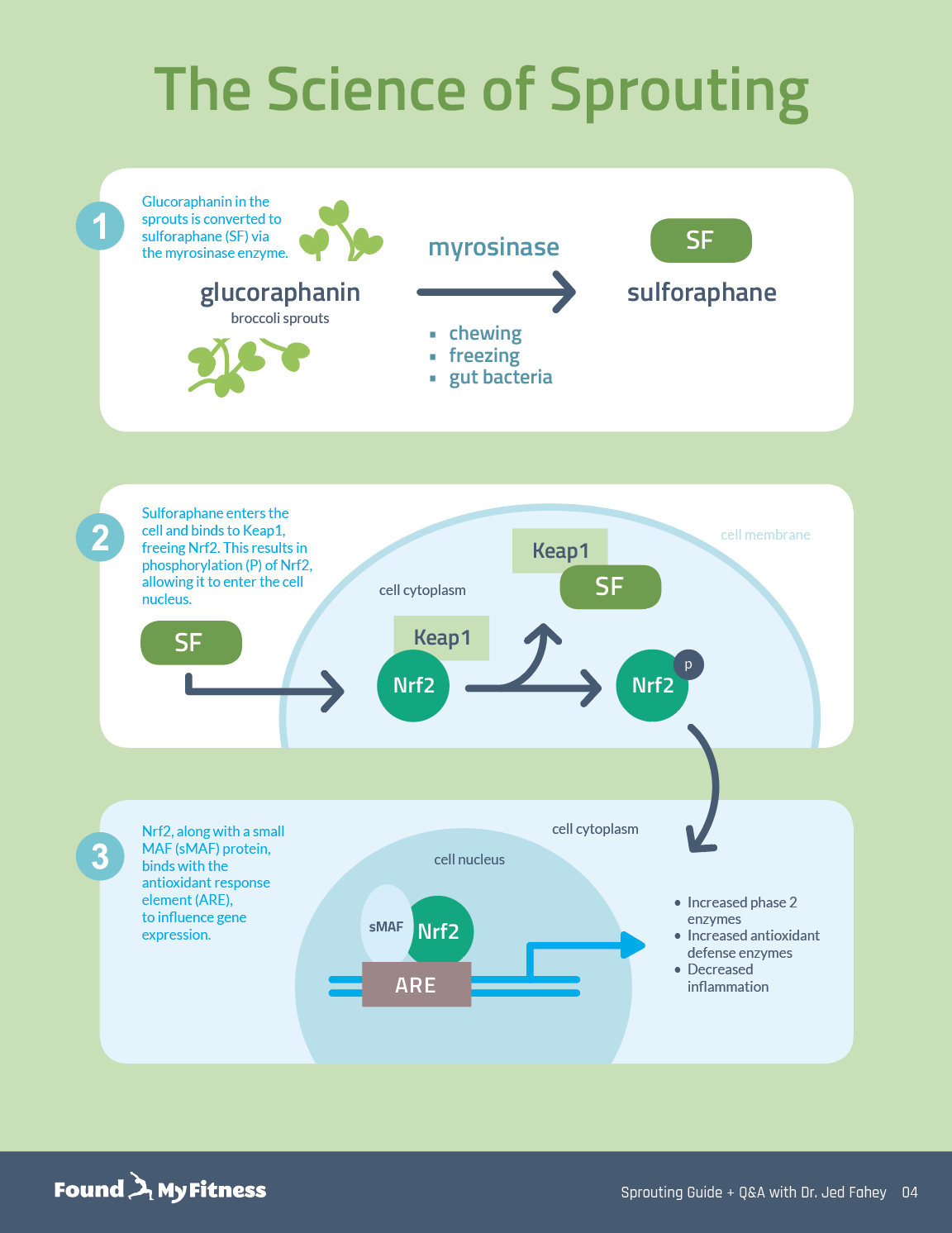

Broccoli sprouts are concentrated sources of sulforaphane, a type of isothiocyanate. Damaging broccoli sprouts – when chewing, chopping, or freezing – triggers an enzymatic reaction in the tiny plants that produces sulforaphane.

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

Moringa, commonly known as horseradish tree or drumstick tree, is a tropical plant widely known for its nutritional and medicinal qualities. A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that moringin, an isothiocyanate compound derived from moringa, may provide protection against chronic diseases, such as cancer and diabetes, and may be useful in treating the symptoms of mental disorders, such as schizophrenia or autism, especially in developing countries. In this episode, Dr. Jed Fahey describes the health benefits associated with moringin and discusses the chemical structure differences between it and sulforaphane.

Jed: And I say that because we're talking about broccoli sprouts and we've been talking a lot about supplements. When you go to the tropics, which is where most of the developing world is, there are plants, and I think I mentioned moringa earlier. Moringa, it happens to be a tropical tree that grows everywhere. It's a weed, and it's also full of an isothiocyanate that is, in many cases, more active than...it may be better than sulforaphane in many situations. Better or worse, but it's sort of on the same level of efficacy of sulforaphane. I'm mentioning that because we've studied it here and I've been involved with actually trying to promote moringa for nutritional reasons. And I've been very fascinated by the potential pharmaceutical or pharmacologic potential of moringa. But it's but one example and there are others that will cite you various other examples of plants that can grow in developing areas of the world, can grow in the dryland tropics, or the wet rainforest tropical regions that could, theoretically, really be game changers not only nutritionally, but in terms of disease prevention in those populations.

And I think we really need to spend, I guess, the preaching part of this, I think we all need to spend more time, and attention, and money on some of those plants. And they may actually have benefit for those of us in the West anyway. I mean, I'm not suggesting that we would want to bring tropical moringa here and try to get people all over the U.S. to eat it because it's got various pharmacologic value to it nor am I suggesting...I certainly wouldn't suggest that we try to cover the world, the equatorial world, with broccoli sprouts because they just won't work. Broccoli is a temperate climate plant and it's too...you know, sprouts are too fragile to import to the tropics or export to the tropics, I think. But the point is that there are plants in various regions of the world that could be adopted, or engineered, or taken over and we should really explore them a bit more, I think.

Rhonda: So I have a couple of questions. So the moringa, does it activate some of the same pathways, different pathways that sulforaphane does?

Jed: It does...

Rhonda: There's a lot of crosstalk... It does?

Jed: Yeah, yeah. So the isothiocyanates have this N double-bond, C double-bond S-group. Again, non-chemists won't care, but that's the active part of the molecule that is responsible for most of its activity, we think. The other part of the molecule that's hanging off that is responsible for solubility and permeability, and contributes to its biological activity. I think it's not as relevant in terms of the activity of the molecule. And so all of the isothiocyanates from cruciferous plants and from moringa all have that NCS group, which is what's responsible for binding to the Keap1 molecule. There are two sulfhydryl groups on reactive cysteines on that Keap1 molecule, and our colleague Dinkova-Kostova has shown that. And the isothiocyanate binds there and causes a change in conformation of that protein. So if you have a different isothiocyanate that maybe is bulkier, maybe it's less effective in getting in that position on the molecule, but, yeah.

Rhonda: Okay. And can we cultivate moringa in places in the United States?

Jed: We can, and it's being cultivated in southernmost Florida and I think even in Southern Arizona and Southern California. It doesn't tolerate frost. So you have to protect it from frost, but, I mean, it's like oranges and lemons and citrus fruit in that respect. So it can be grown in the States. And there are people...I'm actually on the scientific advisory board of a company that's producing moringa in Ghana in Africa. They produce in women's cooperatives and they produce in a responsible way, and they are very attentive to cleanliness of the product that's coming back and they have something that they sell in the U.S. They put it in bars, and they put it in drinks, and they sell the powder plain. There a number of companies that do that.

Rhonda: I've seen it at Whole Foods.

Jed: Yeah, yeah.

Rhonda: Moringa, yeah.

Jed: Yeah, I think in fact...

Rhonda: It was in health food stores.

Jed: Yeah, yeah. There are also some really lousy companies that are producing moringa. There's a multilevel marketing company that's producing it and making outlandish claims. So as with dietary supplements...

Rhonda: Do you have like a list of...do you know which ones are more reliable based on...

Jed: Well, the company that I'm fond of is called Kuli Kuli.

Rhonda: Kuli Kuli?

Jed: K-U-L-I K-U-L-I, yeah. And I think that...

Rhonda: And they make in the United States or they have...

Jed: No, they produce it outside of the United States. They bring it in.

Rhonda: Oh, they are importing, okay.

Jed: Yeah, there probably are companies that are producing it in the U.S. I'm sure there are. As with nutritional supplements, you have to be very careful of claims that are made and what's really in it. So there's a company, I think the biggest company that's been identified with moringa. I'm blanking on the name of the company, but they made a drink and they're a multilevel marketing company and they made many, many irresponsible claims. They invoked the name of Johns Hopkins even in some of their advertising and frankly, I hope they're not doing well. So you just, you have to be careful.

Rhonda: Okay. Another question just to get back to some of what you were initially saying about how this plant, which is growing in some of these tropical regions in more developed nations and how it can be very powerful in cheap dietary intervention that may make a huge difference in people's health in those nations. It just came to my mind knowing what I know about sulforaphane and how sulforaphane is very powerful, and this has been shown in multiple clinical studies, to immediately start to detoxify air pollutants that were exposed to, like, benzene, alkaline, but benzene is a big one. Like, I mean, you start to excrete benzene by, like, 60% after just 24 hours of taking broccoli sprout extract. And I'm thinking about developing countries, there's been a few studies coming out recently that the air pollution and some of these things are a big problem over there, and it's been shown to cause very high stroke risk in young people even because these things are inflaming the blood vessels. It's not just benzene, it's particulate matter and things like that, as well. But still, what's very interesting, if moringa would also be activating these phase II detoxification enzymes, which would be getting rid of some of this compounds and even playing a powerful role in just reducing inflammation in the body and preventing people from having strokes at such young age. So you're right. I think it is very important. You know, people here in the U.S., there's a very large population of people that are interested in aging well and not degenerating and I'm part of that group.

Jed: We all are.

Rhonda: But there is also people that have serious risks that are living in countries where they don't have the luxury of going to a health food store and eating kale smoothies and things like that.

Jed: Exactly, exactly.

Rhonda: So that's really cool that you're involved in that research and advocating for that, as well.

Jed: Well, I think, I actually got involved with a not-for-profit back in the early 2000s that was advocating the use of moringa from a nutritional perspective and I've sort of stayed in touch with that group ever since. And there was a lot of effort to try to get some clinical trials based on its nutritional benefits. It's very high, the leaves are very high in protein, way higher than kale, or broccoli, or most other leafy green vegetables.

Rhonda: Yeah, that's interesting.

Jed: Yeah. And it's also the leaves stay on the trees longer than just about anything else in cases of drought. But there was not the uptake to do a clinical trial, and now there is so much sort of dogmatic promotion of moringa for its nutritional value in those areas of the world that it's so widely used now that I think it's going to be difficult to get some of the rigorous Western-style clinical trials done that we might desire because everybody is just assuming that it's nutritionally, it's a panacea.

Rhonda: And where is it being used mostly?

Jed: Really, all over the tropics, certainly in the Philippines, in large swaths of West Africa and South Africa and in India. I mean, its origin was in northern India near the Pakistan border and it spread around the world since. It spread a long time ago, but it spread around the world from those points of origin all over.

Rhonda: Do people just eat the leaf? Like, how are they preparing? What are they doing? Do they make moringa smoothies?

Jed: Well, some people do. It's interesting, but moringa, because it's sort of a ratty-looking tree, I mean, it's a 20, 30, 40-foot tall tree, but it's sought of ratty-looking and it's sort of hardscrabble. Yeah, it's not gorgeous and the leaves... It was called the horseradish tree or the drumstick tree. Drumstick tree because it has long seed pods that look like drumsticks. Horseradish because it's stringent.

Rhonda: Does it taste like horseradish?

Jed: Yeah, it's harsh. It's sort of like eating Japanese radish, daikon. So, because...and I can give you some to try if you'd like later.

Rhonda: I would, actually. Love to try it.

Jed: Okay, yeah. Because of that harsh taste... Actually, I have some on my shelf right over there. Because of that harsh taste and because of the way it sort of grows like a weed, it's regarded in a lot of areas as a famine food. And it has also been sort of a last resort in cases where people are starving. And from what I understand from my social and behavioral science colleagues, many times, plants like that sort of get a stigma attached to them. So people with little excess money, people who are doing okay may reject what are thought of as famine foods as sort of low class when they don't need them.

So getting people to voluntarily adopt a food like that may be difficult and has proven to be difficult in some areas, and apparently that's one of the reasons. However, it's quite widely eaten, the dried powdered leaves are very easy to store so they maintain their high protein content for a long period of time. That is not the case with things like spinach and kale and some other green leafy vegetables. I mean, imagine drying iceberg lettuce leaves and powdering them and then having them later, yuck.

So in the tropics, dried powdered moringa leaves are found in a lot of areas and are used in food. It's funny, the "Hopkins Magazine" just did a little profile on our involvement with moringa and they quoted me as talking about the first time I had cooked moringa in Africa, which was in Ghana at an international moringa meeting and it was moringa leaves... So I'd had them powdered and I'd had the supplements made from them back in the U.S. But this was in 2006, I think. There was a stew and it looked sort of like saag, like Indian saag, like spinach stew, had some chunks in it. And I was offered some at this meeting on the shores of the Atlantic, a beautiful scenery under sort of tiki huts. And I ate it and then I asked my hosts what the chunks were and it was rat. So I was a little grossed out by my first sampling of moringa made as it's eaten locally, but I actually...

Rhonda: Tastes like chicken?

Jed: Tastes like chicken? Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Rhonda: Wow, I don't know if I could stomach that, especially after experimenting on rats. So these leaves are high probably in also other micronutrients, folate, magnesium.

Jed: They are. They are.

Rhonda: You know, but what's the glucosinolate that is stored in the moringa, what is it called?

Jed: It's called glucomoringin.

Rhonda: Glucomoringin? That's a name I'll have to remember.

Jed: Yes, the lengthy scientific term is 4-L-alpha-rhamnosyloxypyranosyl-benzyl glucosinolate, so there.

Rhonda: Wow. I'll go with Glucomoringin.

Jed: So, you probably prefer the shortcut, yeah.

Rhonda: And what's the active... Oh, that's the isothiocyanate?

Jed: That is the glucosinolate and it's hydrolyzed by myrosinase that's present in moringa leaves to moringin, or for 4-L-alpha-glucopyranosyloxy benzyl isothiocyanate. So it's got a big, honking sugar group, a rhamnose sugar group, and a benzyl group attached to this NCS.

Rhonda: Okay.

Jed: So it's actually, structurally, it's very different because it's got a lot of excess chemical baggage. So in terms of steric hindrance getting to a protein, getting to a molecular site, it's quite different. But as I said before, it's actually more active in some assays and less in others.

A test used in laboratory medicine, pharmacology, environmental biology, and molecular biology to determine the content or quality of specific components.

An aromatic hydrocarbon compound produced during the distillation and burning of fossil fuels, such as gasoline. It is also present in the smoke from forest fires, volcanoes, and cigarettes. Benzene is a carcinogen that targets the liver, kidney, lung, heart, and brain and can cause DNA strand breaks, chromosomal damage, and genetic instability.

Any of a group of complex proteins or conjugated proteins that are produced by living cells and act as catalyst in specific biochemical reactions.

A type of water-soluble B-vitamin, also called vitamin B9. Folate is critical in the metabolism of nucleic acid precursors and several amino acids, as well as in methylation reactions. Severe deficiency in folate can cause megaloblastic anemia, which causes fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath. Certain genetic variations in folate metabolism, particularly those found in the 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene influences folate status. Inadequate folate status during early pregnancy increases the risk of certain birth defects called neural tube defects, or NTDs, such as spina bifida, anencephaly, and other similar conditions. Folate deficiency and elevated concentrations of homocysteine in the blood are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Low folate status and/or high homocysteine concentrations are associated with cognitive dysfunction in aging (from mild impairments to dementia). The synthetic form of folate is called folic acid. Sources of folate include most fruits and vegetables, especially green leafy vegetables.

A glucosinolate (see definition) found in certain cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and mustard. Glucoraphanin is hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase to produce sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate compound that has many beneficial health effects in humans.

Plant secondary metabolites found primarily in cruciferous vegetables. Glucosinolates give rise to a variety of compounds that have been identified as potent chemoprotective agents in humans against the pathogenesis of many chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disease, among others. These products are responsible for the pungent aroma, sharp flavor, and the “heat” commonly associated with some cruciferous vegetables such as wasabi and horseradish.

A critical element of the body’s immune response. Inflammation occurs when the body is exposed to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. It is a protective response that involves immune cells, cell-signaling proteins, and pro-inflammatory factors. Acute inflammation occurs after minor injuries or infections and is characterized by local redness, swelling, or fever. Chronic inflammation occurs on the cellular level in response to toxins or other stressors and is often “invisible.” It plays a key role in the development of many chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Byproduct of a reaction between two compounds (glucosinolates and myrosinase) that are found in cruciferous vegetables. Isothiocyanates inhibit phase I biotransformation enzymes, a class of enzymes that transform procarcinogens into their active carcinogenic state. Isothiocyanates activate phase II detoxification enzymes, a class of enzymes that play a protective role against DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species and carcinogens. Examples of phase II enzymes include UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, sulfotransferases, N-acetyltransferases, glutathione S-transferases, and methyltransferases.

Vitamins and minerals that are required by organisms throughout life in small quantities to orchestrate a range of physiological functions. The term micronutrients encompasses vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids, essential fatty acids.

Also known as the drumstick tree or the horseradish tree. Moringa oleifera is rich in protein, micronutrients, and glucosinolates and is associated with a wide range of health benefits. It is a fast-growing, drought-resistant tree, native to the southern foothills of the Himalayas in northwestern India.

A family of enzymes whose sole known substrates are glucosinolates. Myrosinase is located in specialized cells within the leaves, stems, and flowers of cruciferous plants. When the plant is damaged by insects or eaten by humans, the myrosinase is released and subsequently hydrolyzes nearby glucosinolate compounds to form isothiocyanates (see definition), which demonstrate many beneficial health effects in humans. Microbes in the human gut also produce myrosinase and can convert non-hydrolyzed glucosinolates to isothiocyanates.

A class of detoxification enzymes that play important roles in the metabolic inactivation and/or biotransformation of endogenous compounds, xenobiotics, and drugs so that they are more easily excreted from the body. Phase II enzymes are typically transferases, such as UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, sulfotransferases, N-acetyltransferases, glutathione S-transferases, and methyltransferases. They are involved in glutathione synthesis, reactive oxygen species elimination, detoxification, drug excretion, and NADPH synthesis. Reduced phase II enzyme capacity or activity can lead to toxic effects and increased risk of certain diseases, including cancer.

An isothiocyanate compound derived from cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and mustard. Sulforaphane is produced when the plant is damaged when attacked by insects or eaten by humans. It activates cytoprotective mechanisms within cells in a hormetic-type response. Sulforaphane has demonstrated beneficial effects against several chronic health conditions, including autism, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and others.

Supporting our work

If you enjoy the fruits of

, you can participate in helping us to keep improving it. Creating a premium subscription does just that! Plus, we throw in occasional member perks and, more importantly, churn out the best possible content without concerning ourselves with the wishes of any dark overlords.

, you can participate in helping us to keep improving it. Creating a premium subscription does just that! Plus, we throw in occasional member perks and, more importantly, churn out the best possible content without concerning ourselves with the wishes of any dark overlords.

Sulforaphane News

- Sulforaphane extends lifespan and healthspan in worms via insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling.

- Paul Saladino, MD explains how we may have overstated the health benefits of plants and especially sulforaphane

- NRF2 much of a good thing (December 2017)

- A pilot trial finds sulforaphane treatment increased glutathione levels in the blood & hippocampus region of the brain in healthy people.

- A new study found sulforaphane (found in broccoli sprouts) improved behavior & social responsiveness in children with autism.